|

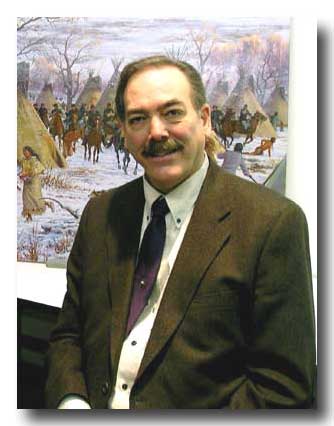

Webmaster's Note: Historian

and Friends member, Jerome Greene, talks with us about his new book Stricken

Field: Little Bighorn Since 1876 (Stricken Field), his career as a

historian, and the Little Bighorn Battlefield today and in the future.

February 2008

Bob Reece: I very much appreciate your taking

the time to discuss Stricken Field: The Little Bighorn since 1876, along

with other aspects of your career for our members and website visitors.

On behalf of the board of directors for the Friends of the Little Bighorn

Battlefield, Iíd like to state that we are excited about this first time

publication, in partnership with the University of Oklahoma Press, of the

limited edition of Stricken Field. I cannot think of a more appropriate

subject for such an undertaking. Stricken Field was originally a study

you conducted for the NPS while you were still a historian in the Denver

Regional Office. What was the purpose of this study?

Jerome Greene: The original purpose of the project was to provide an

updated treatment of the administrative history of the park since publication of

Don Rickeyís History of Custer Battlefield in 1967. In discussions with Neil

Mangum and others, it was agreed that it made more sense to revisit the older

period, as well, now that we had more access to records from that time, as well

as more materials. So it was decided, essentially, to research and write a full

and comprehensive history of the park to include all the new material that had

come to light about the early years, as well as the history that had transpired

there since the 1950s, when Rickeyís study largely ended.

B. R. How does this report help with administration at Little Bighorn

Battlefield National Monument (LIBI)? In other words, how should they use it?

J. G. Hopefully, the superintendent and staff will read the study and

gain a better knowledge of the history of the place, particularly the

administration under the War Department and the National Park Service. That

perspective should help and guide them in making decisions that might be made

routinely in a day-to-day sense, as well as in important decisions affecting

modern policy considerations for the long-term future of the park. It will also

provide a perspective on past problems and how they were dealt with by past

administrators, as well as offer clues to dealing with problems in the future as

they affect, say, the situation regarding the existing land base.

B. R. Did you make any changes for this publication from the original

report, if so what were some of the changes?

J. G. There have been few changes, mostly regarding terminology and words

that were changed editorially while the book was in press. Reviewers of the

manuscript suggested that I speak out more definitively regarding the future

protection of the battlefield resource as well as the surrounding landscape, and

I responded because I believed that it was fully warranted to comment on behalf

of the future of this perennially threatened resource.

B. R. Even though 95% of Stricken Field is not about the battle,

but about the administrative history of the battlefield, there is no doubt in my

mind that the most ardent student of this subject will be amazed with what they

learn from this study. Would you give us an example of a surprising item you

discovered while researching this project?

J. G. I had not known that the project to recover

the officersí remains

in 1877 proceeded (initially, at least) rather secretly and as something of a

cover-up. It was Samuel F. Staples, whose son died with Custer, who protested to

his congressman the blatant favoritism shown officer remains over enlisted

remains. Staplesís obviously angry complaints to Representative William W. Rice

got the ball rolling that ultimately got General Sheridanís attention and

resulted in the place being declared a National Cemetery in 1879. There were

other surprises, too, but that was very significant in the early history of the

site and was likely the key development to what became Custer Battlefield

National Cemetery, ultimately Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. I

think that Mr. Staples deserves appropriate recognition for what he did.

B. R. Stricken Field is not the first book to look at the history

of the battlefield. Don Rickey wrote the first one. But, for the first time, we

have the opportunity to follow all the changing arcs in administering the

battlefield into the 21st century. What, in your opinion, is the most important

change to occur at the battlefield from its administration?

J. G. Without question, it was the construction and dedication of the

Indian Memorial. This at

once made the park (and story) more inclusive and at last reflected the maturing

of American society respecting this site and, at long last, commensurate

recognition and acknowledgement of the Indian participants by the federal

government.

B. R. What do you hope readers of Stricken Field gain from

the book?

J. G. Theyíll gain an understanding of the history and the problems that

have beset the place through decades, but also of how the park reflects the

times and how change occurs, albeit slowly. Readers (as well as administrators)

should also take away an appreciation that this very small, delicate plot of

land is constantly buffeted and must be treated well and intelligently if it is

to survive in any recognizable way for future visitors to study and enjoy.

B. R. In Stricken Field you report on the challenges and

difficulties the NPS has faced over the years with attempts to

expand the

current boundaries. Do you ever see the Monumentís boundaries stretched and what

will it take (besides Congressional action) to make it happen?

J. G. It will take a combination of fortuitous circumstances and special

visionary individuals coming together to provide benefits for all parties and

all the people. I feel that members of the Montana congressional delegation

could lead the way if they truly wanted to act to benefit the site and all

people. At the least, a productive and hopeful dialogue on the part of NPS and

the Crows, looking to include congressional representatives when a positive

juncture arises, could help ease the logjam. However, as I said, I think it will

take very special individuals with remarkable diplomatic skills, working almost

daily on these issues, for anything positive ever to happen.

B. R. In your opinion, what critical issue(s) does the NPS face in

managing the battlefield over the next 25 years?

J. G. Virtually the same ones propounded in the last several

master/general management plans regarding land base, maintenance/development,

view shed, and soaring visitation. Interpretation, however, has made incredible

strides, thanks in large part to the Indian Memorial.

B. R. Letís change the subject a bit and look at your career as a

historian. What happened in your life that made you interested in history?

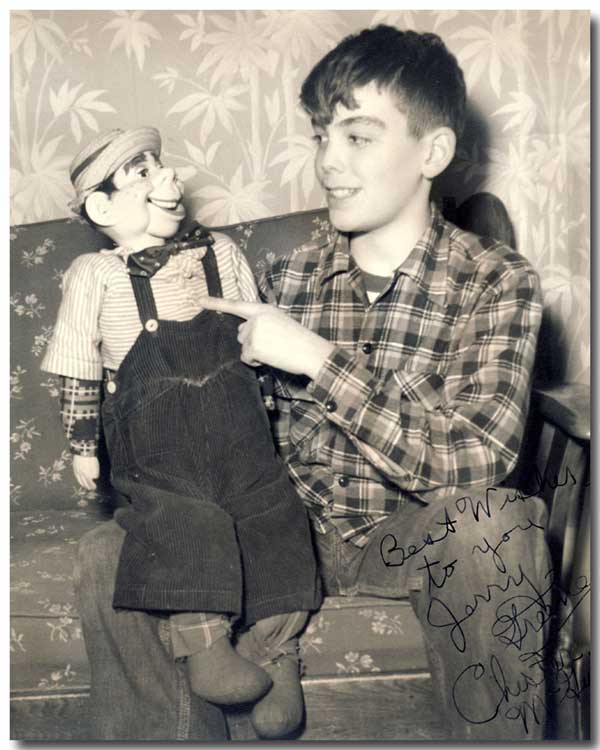

J. G. Actually, I started out to become a ventriloquist. Can you imagine

how that might have turned out? Seriously, I think I became interested in stamp

collecting when I was in grade school, and I really took a liking to historical

commemoratives. As a kid, I also became passionately interested in Indians, and

my parents bought me books and kits to make headdresses, dance bustles,

breechclouts, and leggings, etc. I even had a wig to wear as I raced around the

neighborhood battling imaginary foes in Watertown, New York. Iím sure our

neighbors thought I was completely nutsóespecially in the winter. And then I

read a book about Custeróand that confirmed that I was nuts. My love of Indians

has been a thread through my life, into and out of college (I taught Indian

history to Indian students at Haskell College in Kansas). An interest in

military history easily accommodated my love affair with Indian history and I

became fascinated by the conflicts between Indians and the army in the West.

Jerome Greene (age 11) & Chesty

B. R. Why did you decide to make history your career?

J. G. Fortuitous circumstances. I wanted to teach history, but when the

job at Haskell collapsed in the wake of the BIA takeover in 1972 (I think), NPS

offered me a position as Research Historian in the Denver office.

Bob Utley and Merrill Mattes (two

legends even back then) made it happen in July, 1973, and I couldnít have asked

for a better career tailored to my interests. I became, essentially, a site

historian, which meant that I had to evaluate historic places around the

countryóincluding Indian wars sites in the Westóand research and write narrative

studies of some of the momentous military encounters in our history. I felt like

Brer Rabbit being tossed into that briar patch. I could not have asked for a

better position, and Iím eternally grateful to Utley and Mattes for making it

happen.

B. R. Where did you get your education?

J. G. When I got out of the army, my interest in Custer, Little Bighorn,

and the Black Hills motivated me to attend Black Hills State College in

Spearfish, South Dakota. I received a B.S. Ed. there in 1968 (after which I came

as ranger-historian to Custer Battlefield, serving there in the summers of 1968,

1970, and 1971). I received my M.A. from the University of South Dakota in 1969

(with a thesis onówhat else? Little Bighorn! Part of that evolved into my first

book,

Evidence and the Custer Enigma: A Reconstruction of Indian-Military History, which drew favorable notice). I then attended the University of

Oklahoma on an assistantship for two years working toward a doctorate in

History. I was fortunate to have as professors Donald J. Berthrong, Arrell M.

Gibson (both leading names in Indian and western history), and Savoie

Lottinville--Lottinville was the director of the University of Oklahoma Press

who also taught a remarkable course on "Historical Writing and Editing"--one of

the best I ever had. Unfortunately, I had to withdraw from OU when my G.I. Bill

ran outóI had kids and needed full-time work. Hence my job at Haskell, which

eventually led to the NPS. (Iíve always regretted not finishing my doctorate,

and have flirted with notions to return and get it in retirement.)

B. R. What processes do you undertake with developing a project and

bringing it to publication?

J. G. I spend considerable time thinking a project through, formulating

itówhat I want to do, determining the nature of the information Iíll need and

where Iíll need to go to find it. Then Iíll read everything in my possession (my

private library) bearing on the topic at hand, then visit the appropriate

repositories for data. I read all I can on the topic before starting the

fieldwork. I then visit the properties and familiarize myself fully with the

sites about which I plan to write. Any outlining I do is in my head. I figure

out an approach, then proceed. Itís worked now through about fourteen or fifteen

books (plus many unpublished NPS studies), and I hope Iíve still got a few more

left in me.

B. R. What gives you the most satisfaction when doing research?

J. G. I think that the research phase is the most challenging and

personally rewarding part of writing history, especially when I am able and

fortunate enough to uncover new sources and find new information. Also, feeling

that Iíve been thorough and interesting in my treatment of a subject, and that

Iíve done the best I can on a topic that is important to meóimportant in an

objective sense when dealing with Indian-army history, gives certain

satisfaction. I try to find and explain the Indian side as fully as I do the

army side, and I like to merge the stories when appropriate. Iím really

fascinated by first-person Indian accounts of their struggles with the army, and

Iíve always striven to incorporate them in my work. When I feel Iíve treated all

such accounts (army and Indian) honestly and fairly, and when readers tell me

that they like what Iíve done, then I feel a great sense of personal

satisfaction.

B. R. You told me that a current long term project youíre

researching is the Wounded Knee fight. A lot has been covered on that subject so

what do you hope will come from your work?

J. G. Thatís a good question. Bob Utleyís book

(Last Days of the Sioux Nation) is the

best and is still my favorite Indian wars book. I think that there are new

soldier accounts about that affair that Iíll try to integrate along with new

Indian accounts that have turned up over the past few decades. Again, itís a

fascinating topic and I enjoy plumbing new materials about it. At this point,

Iím not certain where my study is headed. Itís all pretty new to me at this

point.

is the

best and is still my favorite Indian wars book. I think that there are new

soldier accounts about that affair that Iíll try to integrate along with new

Indian accounts that have turned up over the past few decades. Again, itís a

fascinating topic and I enjoy plumbing new materials about it. At this point,

Iím not certain where my study is headed. Itís all pretty new to me at this

point.

B. R. Are there other projects that you can share with us?

J. G. I have a few articles in the worksóone a diary of a soldier in the

Nez Perce War, another piece about Chief Gallís surrender at Poplar River,

Montana, in 1881. Another book manuscript is on the publishing horizon, but itís

yet too early to discuss in any detail.

B. R. If a young adult came up to you and asked you for advice on

what they should consider before becoming a historian, how would you respond?

J. G. Iíd say, simply, ďPursue your heart, pursue your interests, and

tailor your education to those ends. If your future indeed lies in history,

youíll gravitate there despite all. In the meantime, read all you can about all

periods of history and about everything else. It all plays together in the end.Ē

(Back

to Top)

|