By Thomas R. Buecker

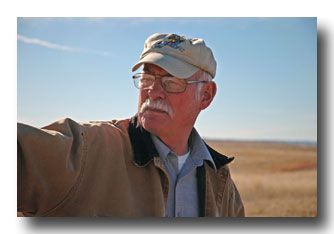

Webmaster's Note: The late Thomas R. Buecker was curator of the

Fort

Robinson Museum at Fort Robinson near Crawford, Nebraska. Mr. Buecker begins his

account of the death of the Oglala-Lakota Crazy Horse in the spring of 1877 when

Red Cloud and his people are located at the Red Cloud Agency near then Camp

Robinson.

The "Final Days of Crazy Horse" first appeared in

Thomas R. Buecker's book,

Fort Robinson and the American West, 1874-1899 copyright

© 1999 by the Nebraska State Historical Society. Red River

Books edition published 2003 by the University of Oklahoma Press, and

appears here by permission of the publisher. This edited version of that

chapter focuses on Crazy Horse.

copyright

© 1999 by the Nebraska State Historical Society. Red River

Books edition published 2003 by the University of Oklahoma Press, and

appears here by permission of the publisher. This edited version of that

chapter focuses on Crazy Horse.

All photos

© Bob Reece 2008, unless otherwise noted

Adjutant's Office and Guardhouse,

Location of the killing of Crazy Horse, Camp Robinson, Nebraska

In the spring of 1877 the situation at Red Cloud

Agency had greatly improved in the army's view. The Indians seemed content, with

adequate food and other annuities arriving regularly. The northern Indians,

subdued by military actions, appeared peaceful and cooperative. General Crook

boasted to Sheridan, “The transition here since last October has been almost

like magic. You could scarcely recognize these Indians now as being the same

people who last spring had such contempt for our government.”

Location of Red Cloud Agency

The army was also greatly relieved with the

surrender of the Crazy Horse band and considered that his capitulation

eliminated a threat of continued war. One band of Minneconjous still worried

army officials; it remained away from its agency, occasionally raiding in the

northern Black Hills country. Nor had Sitting Bull surrendered, but his

activities were farther north and a problem for the commander of the Department

of Dakota, not for Crook.

Peace at Red Cloud led to a troop reduction at Camp

Robinson. It had become exceedingly difficult to maintain the horse herds of the

large cavalry force at the post. The agency traders, both of whom had hay

contracts for the large number of army horses, had failed to deliver. Trader J.

W. Dearcould furnish only thirty-eight of the three hundred tons for which he

had contracted, and Yates, his counterpart, was short over two hundred tons.

Rather than incurring the expense of shipping hay from Cheyenne, a troop

reduction was ordered. On May 26, 1877, less than three weeks after Crazy

Horse's arrival, Mackenzie's Fourth Cavalry battalion-five hundred enlisted men

and officers-departed for its former stations in the Department of the Missouri.

The next day Lt. Col. Luther Bradley arrived from Omaha Barracks to assume

command of the District of the Black Hills and the post. By summer Camp

Robinson's garrison numbered about four hundred men, comprising three companies

of infantry and four of cavalry.

Looking north toward Fort Robinson

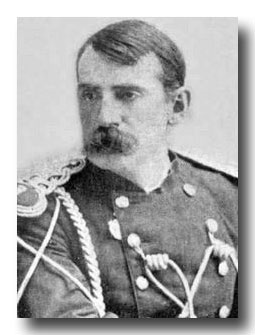

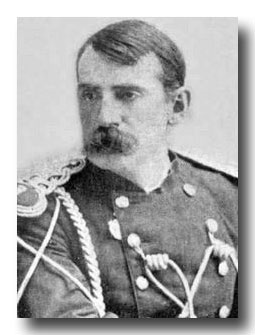

Luther Prentice Bradley began his military career late in 1861 as the lieutenant

colonel of the Fifty-first Illinois Infantry. He later commanded the regiment

through the Chickamauga-Chattanooga campaigns and then on to Atlanta. In July

1864 he was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers, a rank he held until

the end of the war. Due to his success as a commander, he was appointed

lieutenant colonel of the new Twenty- seventh Infantry under the regular army's

postwar reorganization. In 1867 he commanded the Bozeman Trail post of Fort C.

F. Smith when his regiment was assigned duty there during Red Cloud's War.

Bradley later transferred to the Ninth Infantry and was stationed with that

regiment at Fort Laramie. After he arrived at Robinson, Bradley observed a

marked change in the disposition of the Red Cloud Indians. Early in June he

wrote that the subdued Indians were "generally quiet & friendly, a marked

contrast in their conduct now & in former years." He added, "I hope it is the

beginning of a new era."

Reduced troop strength meant that parts of the temporary cantonments built the

previous fall became surplus. The unused structures were demolished for their

lumber. Also available, sitting unused, was quartermaster and ordnance equipment

from the fall troop buildup, such as harness, tools, and stoves. The department

chief quartermaster decided to dispose of everything and printed and distributed

notices of the impending surplus sale around the area, some sent as far as

Sidney and North Platte.

Agency relocation became a pressing issue that

spring for both agency Indians and the new northern arrivals. Some months

previous Sheridan had suggested to Crook the moving of the Indians to new

agencies on the Tongue River and in the Yellowstone country. Although he

initially opposed this idea, by 1877 Crook became one of its strongest

proponents. He believed agencies in the Yellowstone country had several

benefits, including good bottom land for agriculture, a navigable river for

supply, and one of the better remaining hunting ranges. More important the

Indians would be far from the Black Hills miners and settlers. Crook envisioned

a large reservation for the Sioux, Arapaho, and Cheyenne, bounded on the west by

the Big Horn Mountains, on the north by the Yellowstone River, and extending to

the east beyond the mouth of the Powder River. Although the Crow tribe, longtime

enemies of these three tribes, lived due west, the newly established military

posts bordering the region could keep the peace.

Crook and his subordinates thought this an

excellent way to keep faith with the agency peoples. Soldier and Indian alike

thought the newly elected "Great Father," Rutherford B. Hayes, would "do more

for the Indians than any who had proceeded him" and might support the move. The

entrenched Indian bureau, however, would find it too difficult to depart from

its established policy.

Crazy Horse Meets General Crook

Crazy Horse joined the main agency leaders in their

desire for an agency in the north. On the day his band surrendered, Crazy Horse

said he wanted a new agency east of the White (Big Horn) Mountains or along

Beaver Creek in the Powder River country. He reasoned that Beaver Creek was in

the middle of "Sioux Country," and Red Cloud Agency was on its edge. At some

time Red Cloud had misleadingly told Crazy Horse that his band would be allowed

to settle anywhere it chose, "if you will go to Washington and make your peace'

with (the Great Father)." As a result, Crazy Horse set his mind to secure a

northern agency for his people, which he stubbornly pursued during his entire,

tenuous stay at Red Cloud Agency.

On May 25 Crook held a council with the Indians of

the northern Nebraska agencies. Beforehand Lieutenant Clark presented his scouts

for Crook's review. At noon several hundred mounted scouts massed east of the

agency stockade, and afterwards the chiefs formed in line, dismounted, and shook

hands with Crook, who for some had only recently been their main adversary. It

was here that Crazy Horse first met Crook.

During the council the Indians spoke in friendly

terms and expressed their desire for a northern agency, not one along the

Missouri River. Some favored a site north of the Black Hills near Bear Butte.

Crazy Horse, who told Crook he was happy to meet him, gave his preference,

adding that "there is plenty of game in that country." Crook then cautioned the

assembly that although he favored the northern agencies, he could not make the

decision for the government, only make a recommendation. He discussed the

formation of a delegation to Washington to settle the issue. To this the chiefs

responded favorably, but firmly reiterated their opposition to any Missouri

River location. The meeting then adjourned. At the council Crook had made much

of the fact that the new Great Father, of whom Crook was personally acquainted,

wanted to meet them. With the general's support and political connections the

agency chiefs held high hopes for the forming of a beneficial, conciliatory

policy with the new president. Nevertheless they returned to their camps,

awaiting their still uncertain future.

The review of Clark's Indian scouts symbolized one

of Crook's key strategies of the Great Sioux War. A master in the use of Indians

as scouts and auxiliaries, Crook believed such employment would "reconstruct all

hostiles who come in that it will be almost an impossibility to force them on

the war path again." In addition to field scouting, the army used enlisted

scouts as agency police. Under Clark's close supervision the scouts preserved

order in the camps and assisted agency employees with ration and annuity issues.

They disarmed and dismounted Indian bands coming from the north to surrender,

helped keep the peace between the whites and the agency young men, and protected

the camps from white horse thieves.

Crazy Horse Becomes First Sergeant,

Company C, Army Scouts

During the summer of 1877 Clark's scouts saw field service, sometimes

accompanying army units from Camp Robinson. Post officers reported the scouts

used good judgment while on field operations and were "efficient and obedient."

With such traditional activities as warfare and buffalo hunting no longer

available, service as army scouts provided a useful outlet and an opportunity to

garner power and prestige. Many young men, including recently surrendered

northern warriors, saw this and readily enlisted, including Crazy Horse and many

of his followers. Although several interpreters strongly opposed his enlistment

and saw it as a "dangerous experiment," Crazy Horse and twenty-five of his

tribesmen enlisted on May 17. As with other scouts, they were issued Sharps

carbines, Colt revolvers, ammunition, and horses. A visiting newspaper

correspondent reported the enlistment of the recently subdued warriors: “A

remarkable scene occurred when these Red Soldiers were sworn into Uncle Sam's

service. They swore with uplifted hands to be true and faithful to the white

man's movement.”

Adding the new recruits Clark organized his scouts

into five companies of fifty men, each commanded by reliable chiefs. Among

others, the Arapaho Sharp Nose, and Sioux chiefs Red Cloud, Little Wound, and

Spotted Tail were ranked as company first sergeants. After his enlistment Crazy

Horse was appointed as a first sergeant and placed in command of Company C. He

was assisted by his headmen Little Big Man, He Dog, and others as sergeants and

corporals.

Red Cloud

Library of Congress -- Public Domain

The army, especially Lieutenant Clark, discovered another use for his scouts,

espionage, which was thought to make impossible any conspiracy by the northern

Indians. Scouts slipped into camps and gathered information, which Clark then

funneled to Crook. In August Clark confidently reported to his general that he

was "keeping a sharp watch, through some of the scouts I can fully trust on both

agencies, and they keep one pretty well posted.” By this means power was gained

over the Indians at the agencies. As later learned, factors other than loyalty

to the army could color any intelligence these spies reported.

The spring brought an additional improvement to the post, a telegraph line. In

1874 General Ord had requested a telegraph line to Camp Robinson from Fort

Laramie, but the secretary of war vetoed his proposal, stating that none could

be built without a specific congressional appropriation. The Sioux war clearly

demonstrated the need for rapid communications, and the matter was reconsidered.

On March 15, 1877, a detail went to build the line. As the wire gradually moved

east from the main line at Hat Creek, an operator kept his office in a tent at

its terminus to expedite telegraphic communications. On April 22 the telegraph

line became operational, eliminating the slow, horseback courier.

The spring surrenders prompted decisions regarding the relocation of the various

tribes at the Nebraska agencies. Regardless of Crook's suggestions and the

desires of the Indians themselves, the Indian bureau never wavered. It still

planned to move the Sioux to new agency sites along the Missouri River as

dictated by the 1868 treaty.

With relatively quiet agencies, the

Indian bureau pushed for the return to authority of their civilian agents. In

February 1877 the commissioner of Indian affairs had wanted civilians to control

all of the agencies except the troublesome northern Nebraska agencies. General

Sherman, in turn, wanted to be consulted before any agencies returned to civil

control. On March 15 division headquarters ordered the civilian takeover,

stating. “[T]he above regulation will take effect at the Spotted Tail and Red

Cloud agencies as soon as civil agents have been appointed hereto." Earlier in

the month Dr. James Irwin, the agent at the Shoshone and Bannock Agency in

Wyoming Territory, was appointed as the new Red Cloud agent. Although he

accepted on March 14, there was a delay of several months before he started the

new assignment. By the summer of 1877 the army was more than ready to exit the

agency business. Lt. Charles Johnson, the last of five officers from Camp

Robinson to serve as acting agent, passed the mantle to Irwin on July 1.

Midsummer brought resumed raiding to the northern Black Hills country. Although

no settlements came under direct attack, travelers were harassed and livestock

taken from ranches in the foothills. It was believed that small groups of agency

holdouts, moving between the Yellowstone River country and the agencies, carried

out the raids. In July Gov. John L. Pennington of Dakota Territory telegraphed

Crook for soldiers.

The trouble in the Hills came at a time of other distractions. July riots in

Chicago forced all available troops stationed along the railroad to be sent

there to keep order. Hard-pressed to send troops to the Black Hills, the

secretary of war was nevertheless later able to report, "[B]y rapid movement,

all that could be was done to have them at all points when I needed."

Captain Weasels’ company scouted in the Spearfish Canyon area. The press failed

to soothe the panicky settlers; one newspaper reported that "at least twenty

murders have been reported....Nearly every ranch along the Redwater and in

Spearfish valley have [sic] been devastated." Another cavalry company sent from

Camp Robinson to scout east of the Hills took along ten of Lieutenant Clark's

Indian scouts, but returned without seeing any raiders or trails. Units from

Fort Laramie also patrolled the Hills. Crook thought that sending out

company-sized units was adequate. He was also very skeptical of the newspaper

accounts and the exaggerated reports of the settlers. “[S]ome of those

frontiersmen are addicted to lying." As it turned out, the raids were the work

of small parties of warriors not from the Nebraska agencies.

Sheridan had long favored the establishment of a military post near the Black

Hills to ease the burden of sending troops from Fort Laramie and Camp Robinson.

In late summer of 1878 a new post near Bear Butte was built to provide permanent

security for settlers. The post, eventually to become Fort Meade, was

established by Maj. Henry M. Lazelle, First infantry, the same officer who had

served in the army's early days at Red Cloud Agency.

In September 1877 the last group of northern Indians came to the Nebraska

agencies to surrender. This was the Lame Deer band of Minneconjous, thought

responsible for most of the summer raiding. On May 7 Col. Nelson Miles had

finally caught up with and surrounded this village of over fifty lodges in the

Yellowstone country. In the ensuing fight Chief Lame Deer and thirteen of his

warriors died. Afterwards, scattered remnants of the village surrendered at Red

Cloud Agency, where Bradley assured them that regardless of the depredations

they had committed, they would be well treated. Finally, on September 11 the

main body surrendered at Spotted Tail Agency.

Crazy Horse, the Celebrity

After Crazy Horse surrendered in May, his people settled into the routine of

agency life. What army officers saw as the "beginning of a new era" with peace

and order at the White River agencies turned into a summer of intrigue,

mistrust, jealousy, and deceit.

For Crazy Horse and most of his followers encamped north of the White River

several miles northeast of Red Cloud Agency, this was their first time at an

agency. The free-roaming days of hunting and war were over; they were now

dependent on the agency system for their daily existence. The army itself

learned how highly regarded in Lakota camp circles the warrior-chieftain was.

Many agency Indians commented on his courage and generosity. The latter trait

earned him much of his popularity; some said he kept nothing for himself.

Lieutenant Bourke once reported, "I have never heard an Indian mention his name

save in terms of respect."

Lt. John G. Bourke said of Crazy Horse,

"I have never heard an Indian mention his name save in terms of respect."

Photo Public Domain

Accompanied by Frank Grouard, the well-known guide and interpreter of Polynesian

descent, Bourke went to Crazy Horse's camp the evening following his surrender.

When they reached his lodge, they found Crazy Horse seated on the ground. Sorrel

Horse, who also accompanied Bourke, told Crazy Horse that Bourke was one of the

officers of "Three Stars." Bourke recounted, [Crazy Horse] "leaned forward,

grasped my hand warmly and grunted ‘How.' This was the extent of our

conversation." Bourke further noted Crazy Horse's countenance, "His face is

quiet rather morose, dogged, tenacious and resolute. His expression is rather

melancholy." Grouard then escorted Crazy Horse to his cabin for supper.

Phil Sheridan voiced his concern about keeping Crazy Horse and other war leaders

at the Nebraska agencies. He wrote Sherman, “A sufficient number of the hostile

Indians have now surrendered to permit us to take up the question of punishing

the leaders with the view of preventing any further trouble." In a continuation

of the policy adopted after the Red River War of exiling southern Plains

leaders, Sheridan evidently sought Sherman's views on sending Crazy Horse and

others to Fort Marion at St. Augustine, Florida. However, the commissioner of

Indian affairs believed these Indians had surrendered in good faith as prisoners

of war and were not necessarily criminals (unless so proven). Sherman somewhat

reluctantly agreed, adding "to send them to St. Augustine they would be simply

petted at the expense to the U. S. Better to remove all to a safe place and then

reduce them to a helpless condition." The Indian leaders of the Great Sioux War

who surrendered at the Nebraska agencies would remain there until the agencies

were moved.

In the meantime Crazy Horse became somewhat of a celebrity. There was great

interest in his role in Custer's defeat at the Little Bighorn. A reporter from

the Chicago Times came in late June to interview him about the battle.

Lieutenant Clark arranged the interview, with Baptiste "Little Bat" Gamier

interpreting, while Horned Horse acted as a spokesman for Crazy Horse. "Horned

Horse told the story readily (after some hesitation), which met with the

approval of Crazy Horse."

White visitors to his summer camp became a fairly common occurrence. One

correspondent remarked that his village presented a better appearance than any

other seen; also Crazy Horse had presented him with a pair of his moccasins.

After Colonel Bradley arrived at Camp Robinson, the Sioux chiefs, including

Crazy Horse, came to the post to meet him. When Bradley was introduced and shook

hands with the warrior-chieftain, he found Crazy Horse "a young slender and mild

mannered fellow.” During these pleasant days Clark, another frequent visitor,

tried to cultivate his friendship. Clark thought he had somewhat succeeded and

reported to Crook that he was on "excellent dog eating terms" with Crazy Horse.

Not all looked favorably on Crazy Horse's new status. Some Indian leaders

believed Crazy Horse was receiving special favors. Resentment and jealousy began

to appear around some of the campfires.

Shortly after his initial council with Crook, Crazy Horse watched the Cheyennes

depart for the southern reservations. He was also hearing the talk of moving the

Sioux to the Missouri River. By midsummer his suspicions of the Indian bureau

had grown. On the other hand, the Cheyenne departure removed a large body of

potential army allies. Due to their supposed ill treatment at Crazy Horse's camp

after the Red Fork fight, Lieutenant Bourke believed many Cheyennes remained

bitter toward Crazy Horse. He also thought Crazy Horse grew more insolent to the

army after the Cheyennes departed.

Crook had promised the agency Indians in the spring that they could go on an

organized buffalo hunt in the north, where sizable herds still remained, but

only after the last northern bands (meaning Lame Deer's Minneconjous)

surrendered. He intended to let the Crazy Horse band participate. Although by

summer the Lame Deer band was still out, the agency Indians wanted to depart

sometime in July. But Crook held firm: the hunt could not commence until the

last northern group surrendered. The army received word in midsummer that the

band was coming in, and it appeared that the promise would be kept.

Resentments Against Crazy Horse

On July 27 a council was held at Red Cloud Agency to discuss preparations. About

seventy agency Sioux attended, including Red Cloud, Crazy Horse, Little Big Man,

and Young Man Afraid of His Horses. Lieutenant Clark read a message from Crook,

who told them that everyone who wanted to go should plan on being gone about

forty days. They were to conduct themselves peacefully, and had to return on the

date specified. Crook would also allow the agency traders to sell ammunition for

hunting. All the Indians present expressed their satisfaction.

As was customary for such councils, a feast was proposed. Agent Irwin would

provide three head of beef, coffee, and other essentials after the assembled

Sioux decided in whose camp to hold it. Young Man Afraid proposed Crazy Horse's

camp. Upon hearing this, Red Cloud and several other leaders immediately arose

and walked out.

That night Irwin and Benjamin R. Shopp, a special inspector for the Indian

bureau visiting the agency, were informed some Indians wanted to see the agent.

Ignoring the late hour, Irwin agreed to meet the persistent visitors, who turned

out to be representatives of Red Cloud's and other bands. They told Shopp and

Irwin there would be great dissatisfaction if the feast was held at Crazy

Horse's camp. Crazy Horse had only recently joined the agency, and "he should

come to them." They explained that holding the feast at his village would

demonstrate the government's disposition to conciliate him at the expense of the

friendly, reliable agency leadership. The delegation also let it be known that

Crazy Horse was "tricky and unfaithful to others and very selfish as to the

personal interests of his own band." If Crazy Horse left on the hunt, he and his

band would return to the warpath. The night visitors only reinforced doubts

about Crazy Horse held by Irwin, who had always opposed the hunt.

Crook lifted the prohibition of the sale of ammunition to the Indians the next

day. Irwin and others at the agency thought it unwise. One officer's wife at

Camp Robinson voiced concern over any renewal of ammunition sales, " [I] n one

day they could get enough to help their northern friends ever so much in their

war with the whites." Apparently Irwin was able to halt the sales at his agency.

Not all Indians favored this hunt. Spotted Tail in particular opposed the plan

and spoke against it to Lt. Jesse Lee, the acting agent at his agency. Along

with Capt. Daniel W. Burke, Camp Sheridan's post commander, Lee thought a crisis

was at hand. If the Indians at Spotted Tail -- Brules and recently arrived

northern Indians -- went on a hunt "with all the wild Indians from Red Cloud,

trouble might ensue and many would slip away and join Sitting Bull, who had gone

north of the line."

Another item on the agenda at the July 27 council was the formation of a

Washington delegation. Crook's message announced the Interior secretary's

permission for representatives to come East and present their views on moving

the agencies to the Missouri. The proposed delegation would leave in September,

and Crook advised the council members to pick their best men to protect their

interests.

Earlier in the spring Clark had told Red Cloud that he and others would make a

trip to Washington to discuss agency relocation. Clark also told the chief that

Crazy Horse, after he came in, would accompany any delegation. Red Cloud later

informed Crazy Horse of this: "The army wants you to go to the Great White

Father," in addition to telling him he would be permitted to select an agency in

the north.

Crazy Horse wanted to go to Washington, provided the government let him have a

northern agency before his departure. As he remarked to one of his headmen,

"When I pick out a land I will pick one right near the Black Hills." He

understood the purpose of the Washington trip was to make peace and to select a

favorable agency site for his people.

The army was keenly interested in having Crazy Horse join the delegation.

Several days after the council Colonel Bradley called both Crazy Horse and

Little Big Man to the post and told them the Great Father wanted to see them.

Little Big Man agreed to go, but Crazy Horse gave no definite reply, although by

this time he was openly telling his followers he would go to Washington only

after the agency site was selected. Bradley, though, firmly told him he must go

to Washington first.

Jealousy by the agency Indian leaders grew daily, some because white people came

to see Crazy Horse and, it was rumored, brought him money. Others feared that if

Crazy Horse went to Washington, he would be made chief of all the Sioux.

Apparently those agency leaders who had long supported the government now

believed they were secondary in stature to Crazy Horse. They feared his

popularity would prove a threat to their power and political status. As this

jealousy permeated the camps, tension grew and factions among the Oglalas at Red

Cloud began to form.

Rifts Within Crazy Horse's Camp

Factions developed in Crazy Horse's own band and damaged old loyalties. For

example, an open rift developed between Crazy Horse and He Dog, a shrewd fighter

and loyal friend, who moved his camp and switched his allegiance to Red Cloud.

Little Big Man, once Crazy Horse's trusted lieutenant, drifted away from his

influence, and some thought Little Big Man entertained aspirations of becoming a

great Sioux chief. In two years he had converted from the fierce warrior who had

broken up the Allison Commission to a willing follower of the whites. With

defections in the northern ranks, Bourke rightly observed, "[T]he weakness of

faction had been made to replace the solidity of harmony." Within weeks only

about half of the band that surrendered in May remained in Crazy Horse's camp.

However, Crazy Horse had one formidable ally. Touch the Clouds, the towering

Minneconjou leader, apparently grew sympathetic to his cause. Standing "six foot

five in his moccasins," his band was among the 1,300 Minneconjous and Sans Arcs

who had surrendered at Spotted Tail Agency in April. As the summer progressed,

Touch the Clouds became a power behind the northern Indians there, as well as an

ardent backer of Crazy Horse in his growing conflict with the Indian bureau and

the army.

Standing: Joe Merrivale; Young Spotted

Tail; Antoine Janis; Seated: Touch-the-Clouds;

Little Big Man; Black Cool, and unidentified

Brady-Handy Collection of the Library

of Congress -- Public Domain

The divisiveness in Crazy Horse's camp did not go unnoticed by Philo Clark, who

turned to his scouts and informants for intelligence. Spies saturated the camp,

all eager to report anything of interest to Clark, true or fabricated. Several

scouts, including Lone Bear and his brother, Woman's Dress, spent increasing

time lounging outside Crazy Horse's lodge, listening and watching. Throughout

Crazy Horse's stay at the agency, "Clark had detectives with ears quick to catch

every word that might fall from Crazy Horse's lips, and eyes keen to note his

every movement." Many Indians concluded the stories the spies told were the

cause for the ill feeling and mistrust that characterized that summer.

Crazy Horse's attitude turned noticeably unfriendly toward both agency Indians

and the whites. Shopp reported he was discontented and "seemed to be chafing

under restraint." He also became recalcitrant toward his fellow tribesmen. By

the end of July Irwin found Crazy Horse acting similarly to his employees, but

the army was unconcerned about the agent's assertions. Earlier Bradley had

boasted to Crook, "[W]e are quiet here as a Yankee village on a Sunday." Clark,

the military's chief contact with Crazy Horse, still had amicable meetings with

him. As the army soon learned, "Concealed beneath the apparent calm, however,

was a growing turbulence among the various camps and their chiefs."

Later on an issue day Crazy Horse refused to sign receipts for his issue items

and made "demonstrations" about the agency. When Irwin reported this to

Bradley, he discovered that "it was hardly credited as the military still had

faith in Crazy Horse." Continuing this pattern of behavior, Crazy Horse refused

his pay at the regular muster of Clark's Indian scouts. When Irwin pressed

American Horse to help secure better cooperation with Crazy Horse, American

Horse told Irwin flatly that he and other leaders could do nothing with him.

In early August Crook pushed his officers at Camp Robinson to convince Crazy

Horse to join the upcoming Washington delegation, but Crazy Horse was less

willing to go than ever. Rumors sprang up in the camps that Crazy Horse would be

imprisoned or killed if he went with the delegation. By August 15 Crazy Horse

had told Bradley he would not go. Two days later Crook sent a telegram urging

Crazy Horse to make the trip. To sweeten the deal, Irwin gave Crazy Horse two

cattle, and Clark bought items at the commissary for a feast. When Clark

approached him about a decision, Crazy Horse replied he would not go, but wanted

his selected headmen to go in his place and to replace Red Cloud, Spotted Tail,

and other friendly Oglala leaders. Clark tried to explain that headmen from all

the bands must go, not just his. This final demand gave Clark the impression

that Crazy Horse intended to dictate policy to the government. On the other

hand, it seems reasonable that Crazy Horse would not trust the agency

leadership, fearing they would consent to an unfavorable agency move as had the

Cheyennes.

Rumors of outbreak and renewed war circulated around Red Cloud Agency, heard as

early as the end of June during the Sun Dance in Crazy Horse's village. One

newspaper warily reported, "Private correspondence from Red Cloud Agency gives

information that since the Sun Dance...a large number of young bucks have gone

back north." Agency employees heard warriors were secretly trading for guns with

freighters and other nonagency types. Shopp noted, “[The Indians] seem

determined to secure arms at all hazards and will exchange property of great

value for them." Clark's spies brought word that Crazy Horse's men were buying

and concealing arms in their camp. One informant saw an Indian exchange four

ponies for a rifle.

While all this information swirled about, the proposed buffalo hunt was

canceled. After the July 27 council, rumors abounded that the northern Indians

would use the hunt as a means to break away. With the friendly chiefs and Agent

Irwin lined up in opposition from the idea's inception, Crook finally relented.

On August 4 ammunition sales were officially halted, and the next day the hunt

was postponed. As word of its cancellation passed through the camps, Bradley

informed department headquarters, "I think there will be no trouble about

postponing the hunt." With no hunt and little word about a northern agency,

Crazy Horse and his still-loyal followers grew even more suspicious.

Crazy Horse's Power Must Be Broken

After Crazy Horse's refusal to join the delegation, Clark lost faith in the

Oglala leader. Clark learned that some of Crazy Horse's supporters had secretly

gone to Spotted Tail Agency to induce the northern Indians to move to his camp.

After digesting the rumors, the reports of his spies, and the counsel of the

friendly chiefs, Clark became convinced that to preserve order at the agencies

Crazy Horse's power must be broken. On August 18 he wrote Crook in frustration,

"I am very reluctantly forced to this conclusion because I have claimed and felt

all along that any Indian could be 'worked' by other means, but absolute force

is the only thing for him."

Crook and some of his subordinates, however, still believed Crazy Horse had good

intentions. That summer Crook sent Capt. George M. Randall, his chief of scouts

during the Sioux war, to Camp Robinson to observe the agency. Randall believed

Crazy Horse wanted to do right but needed time to become more conciliatory

toward the whites. Randall told Lieutenant Lee at Spotted Tail Agency that Crazy

Horse was "buzzed too much" by prominent Oglalas at the agency.

As these events transpired at Red Cloud, Crook had other distractions. After

leaving Camp Robinson in late May, he spent much of July touring the Big Horn

and Yellowstone country with generals Sherman and Sheridan. Both senior generals

were anxious to see the Sioux War country, and Sheridan wished to visit the

Custer battlefield. As the tour neared its completion, railroad strikes broke

out in Chicago; federal troops were called to restore order. On July 27

Sheridan, accompanied by Crook, quickly returned to Chicago to take stock of the

situation.

As this urban problem died down, another crisis was brewing on the frontier. The

Nez Perce tribe, headed by Chief Joseph, had begun its epic outbreak in the

Northwest. The month of August saw the fugitive Nez Perce nearing the borders of

the Department of the Platte, which naturally concerned Crook. On August 23

reports came in that Joseph had entered Yellowstone Park in his department.

Although it was not known where the Nez Perce would go next, Crook was ordered

to prepare an expedition to head them off. To supplement his troops in the

field, he mobilized the Sioux scouts at the Nebraska agencies. At Camp Robinson

Lieutenant Clark had to organize at least one hundred scouts for field service.

Outside events had always affected matters at the agency and the army camp, and

now the stage was set for the final chapter in the Crazy Horse saga.

"Until There Is Not A Nez Perce" Left

On the evening of August 30 Clark held a council with the agency leaders,

including Crazy Horse and Touch the Clouds, to explain Crook's need for scouts

and to ask their cooperation. Many of those present were willing to join the

fight against the Nez Perce. The northern Indians and Crazy Horse, however, were

receiving contradictory messages; they had surrendered and had been asked to

make peace, and now they were being asked to make war.

The next day Crazy Horse spoke and expressed his

displeasure that the hunt had been canceled, but he added that he and his men

would join the soldiers against Joseph. In his interpreting, Frank Grouard

garbled the translation and made a grave mistake. He rendered Crazy Horse's

reply as saying, in effect, that Crazy Horse would fight until no white men were

left, when he probably meant "until there is not a Nez Perce" left. Louis

Bordeaux, another interpreter, noticed the slip and immediately pointed out the

error to Grouard, who abruptly left the council. Clark had the reliable Billy

Garnett finish the interpreting, but the damage had been done. To Clark it

appeared Crazy Horse was threatening war.

Before the council broke up, Crazy Horse told Clark that he would leave with the

scouts, but he wanted to bring his whole camp along and do some hunting. Clark

would have nothing to do with this proposal, which effectively ended their

discussion.

Crazy Horse's misinterpreted statement at the council only reinforced the

outbreak rumors Clark had heard. It was also reported -- and feared -- that Crazy

Horse would persuade others, including enlisted scouts, to join his departure.

The army estimated that if Crazy Horse left, some two thousand northern Indians

at the agencies would accompany him.

Some have argued that the possibility of Crazy Horse and his followers breaking

away was highly unlikely. After their surrender, they had lost most of their

horses and arms, but the rumors of illicit firearm sales persisted, and some

warriors enlisted as government scouts had actually rearmed. Neither the Indian

bureau nor the U.S. Army wanted to risk renewed conflict. Crazy Horse could

easily create trouble, "and he gave every evidence that he intended to do it."

Sheridan, advised of Crazy Horse's growing defiance, was now keenly aware that a

dangerous situation was germinating at the agencies. As he awaited developments

in his Chicago headquarters, Crook headed west by rail to direct operations

against the Nez Perce. Sheridan hoped the scouts would go as soon as possible to

augment the planned expedition against Joseph. By August 31 Bradley had the

scout detachment, including scores of new, eager volunteers, ready to move out

when an explosive complication to their deployment arose.

Several days earlier word had filtered out that Sitting Bull's band had left

Canada to help Chief Joseph fight the whites. Many in the agency camps presumed

that the scouts were to be sent out against Sitting Bull instead of Joseph. Also

on August 31 Crazy Horse and Touch the Clouds allegedly told Clark that they

were no longer going to stay at the agencies; they were leaving with their

people for the north. This rumor created considerable excitement among the

agency Indians. Bradley quickly telegraphed his superiors, "I think the

departure of the scouts will bring on a collision here." He also requested

Crook's presence at the agency, " [I]f anyone can influence this Indian [Crazy

Horse] he can."

The Time Has Come To Remove Crazy Horse

Sheridan quickly responded and ordered Bradley to delay deploying the scouts. He

telegraphed Crook, still on board the train heading toward the Wind River

country in Wyoming, to go to Red Cloud instead. Sheridan was convinced the

growing crisis required Crook's personal attention. Crook, on the other hand,

did not initially concur. But Sheridan now made it clear, "The surrender or

capture of Joseph...is but a small matter compared with what might happen to the

frontier from a disturbance at Red Cloud." The time had come, Crook realized, to

break up the Crazy Horse band and remove its leader from the agency.

From an eastern Nebraska railroad stop, Crook sent word to Bradley to surround

and capture the camps of Crazy Horse at Red Cloud and of Touch the Clouds at

Spotted Tail. He cautioned, "Delay is very dangerous in this business."

Meanwhile Bradley had quietly called in reinforcements; within two days, four

additional Third Cavalry companies rode in from Hat Creek and Fort Laramie.

While Crook detrained at Sidney and headed north, the agency chiefs reassured

Irwin and Clark that they would side with the government in case trouble

erupted.

Clark warned Lieutenant Lee at Spotted Tail to beware of treachery by Touch the

Clouds and advised Captain Burke that the capture of both camps was planned.

This came as a surprise to Lee and Burke, who had always found the tall

Minneconjou extremely cooperative and thought it highly unlikely he could be

instigating problems at Red Cloud. Burke immediately called in Touch the Clouds

for a council to confirm his loyalty. Touch the Clouds denied threatening war

and explained the misinterpretation when Crazy Horse was asked to scout against

the Nez Perce. Convinced of Touch the Clouds's good intentions, Lee hurried to

Camp Robinson to explain his side of the story to Clark. When he arrived at the

post on September 2, Crook was already there, planning the capture of the two

belligerent camps that same night.

An Assassination Plot Against Crook?

Crook wanted Spotted Tail's followers to ride with the troops from Camp Sheridan

to surround Touch the Clouds's camp, while Red Cloud Indians assisted the Third

Cavalry against the Crazy Horse band. To insure success, the chiefs were told to

select only their best men for the operation. But often the best laid plans go

awry. Later that day word came of the approach of the Lame Deer band, and Crook

immediately delayed the action.

In hopes of giving Crazy Horse "one last chance for self-vindication," Crook

called him to a council on the morning of September 3. While Crook rode with

Clark in an army ambulance to the meeting, the Indian scout Woman's Dress

suddenly rode up and warned the general of an assassination plot. While

eavesdropping outside Crazy Horse's lodge the night before, the scout claimed to

have heard Crazy Horse tell his men he would kill Crook at their meeting. This

revelation prompted Crook and Clark to hurry back to Camp Robinson and safety.

Subsequent evidence indicates that Woman's Dress and other enemies of Crazy

Horse fabricated the assassination story. One contemporary labeled this

conspiracy, "a shrewd plan, skillfully worked and shamefully successful." Billy

Gamett for one, a reliable source, claimed that it was all a lie. Gamett said he

was present at an 1889 confrontation with Woman's Dress where the plot was

exposed as a frame-up against Crazy Horse by jealous rivals. Unfortunately

Crook "gave full credit to his story." True or not, Woman's Dress's tale forced

the army's hand: Crazy Horse must be removed.

When Crook returned to the post, he ordered Bradley

to capture Crazy Horse's village the next morning, even with the Lame Deer band

still some distance away. Crook no longer considered Touch the Clouds a threat,

and directed his attentions to the capture of Crazy Horse.

Crook's Secret Meeting At Camp

Robinson

According to some accounts, Crook and Clark held a secret meeting at Camp

Robinson that afternoon with certain chiefs considered reliable, including Red

Cloud, Young Man Afraid, American Horse, and No Water, the latter an avowed

enemy of Crazy Horse. Crook told them Crazy Horse was leading their people

astray and they must help the army arrest him. The Indians purportedly proposed

to kill Crazy Horse, an idea Crook immediately vetoed. He told them that if they

and their followers helped in his capture, it would prove they "were not in

sympathy with the non- progressive element of their tribe." The agency leaders

readily agreed to march with the soldiers the next morning.

Early on the morning of September 4, confident that the situation at Red Cloud

was well in hand, Crook turned his attention to the Nez Perce and departed for

Cheyenne to resume his trip to Camp Brown, Wyoming Territory. Several hours

earlier an anxious Lee rushed back to Spotted Tail Agency to prepare for any

collateral trouble that might erupt. At nine o'clock four hundred cavalrymen,

three hundred Sioux, and one hundred Arapahos rode to the Crazy Horse camp.

Before reaching their destination, some of the Indians unwisely fired at a

coyote running along the river bank. The brief fusillade alarmed nearby camps,

who believed the soldiers were attacking Crazy Horse. When the large contingent

reached the camp, the soldiers found it nearly deserted. Their Indian allies

pursued and captured most of the fleeing inhabitants, who were to be

redistributed among other bands, where "the people will be subjected to better

influences."

Much to their chagrin, Bradley and Clark discovered Crazy Horse had fled the

camp before daybreak. Taking his wife, and possibly accompanied by several

others, he had departed for Touch the Clouds's camp. As Bradley contacted

department headquarters with news of this setback, Clark quickly dispatched

twenty of his Indian scouts under No Water to overtake Crazy Horse and dashed

off a message to Lieutenant Lee to arrest Crazy Horse if he arrived at Spotted

Tail Agency. Clark also warned Lee to keep matters quiet at his agency and to

intercept any Crazy Horse followers that might show up.

At four o'clock that afternoon a great commotion broke out in Touch the Clouds's

camp when a courier dashed in and reported fighting at Red Cloud Agency;

soldiers were on the way. As order was restored, Lee received the startling news

that Crazy Horse was in the camp. About this time the scouts sent to pursue

Crazy Horse rode in, adding to the chaos. Major Burke and Lieutenant Lee

immediately set out for Touch the Clouds's camp, three miles north of Camp

Sheridan. They were met by several hundred northern warriors escorting Crazy

Horse to the camp.

After they reached the post, Crazy Horse told Burke and Lee that he had left Red

Cloud to get away from the troubles there. Meanwhile Spotted Tail and three

hundred of his followers arrived at Camp Sheridan, adding to the gathering

throng. The powerful Brule chief tersely informed his fugitive nephew that this

was his agency and ominously added, "I do not want anything bad to happen to you

here." Desiring a more quiet place to talk, the officers took Crazy Horse into

Burke's quarters, where Crazy Horse told them he wanted no trouble and wished to

be transferred to the Brule agency.

“They gave me no rest at Red Cloud. I was talked to night and day and my brain

is in awhirl.” He added, "I want to do what is right."

The officers explained that they had no objection to his transfer if what he

said was true. Burke and Lee then advised him to return with Lee to Camp

Robinson, where "his good words would be told there, that he could tell them

himself," to smooth over his difficulties. They reassured him this was his best

and only course. Crazy Horse agreed and went back to the Minneconjou village

with Touch the Clouds, who assured Burke that Crazy Horse would not escape

during the night. After the Indians left, Lee sent a courier to inform Clark

that he would bring Crazy Horse to Camp Robinson the next day.

Crazy Horse Rides Into Camp Robinson

As Wednesday, the fifth of September, dawned, Crazy Horse developed second

thoughts. About 9 A.M. he went to Lee and stated that he feared trouble at Red

Cloud and that he had changed his mind about returning. The persistent officers

bluntly told him to go quietly to Camp Robinson and explain matters there -- it was

the only thing to do.

Right after this meeting, Crazy Horse and a small party left Spotted Tail Agency

for the forty-mile trip to Camp Robinson. Lieutenant Lee, the interpreter

Bordeaux, and several Indians, including Touch the Clouds, rode in an army

ambulance; according to his wishes, Crazy Horse traveled by horseback. Several

other reliable agency Indians rode along. As the curious entourage made its way

westward, it was gradually joined by small groups of mounted Indians. Eventually

fifty of Spotted Tail's warriors escorted Crazy Horse.

Clark received Lee's message early that morning and sent word to Crook at

Cheyenne that Crazy Horse was coming in. Upon Crazy Horse's arrival he would be

held under guard in the post guardhouse until nightfall, then whisked off to

Fort Laramie. Clark suggested sending several of his followers along to assure

Crazy Horse's people of his safe passage. He added optimistically, "Everything

quiet and working first rate."

On receiving these recommendations, Crook ordered Bradley to send Crazy Horse

with several of his men under strong escort to Laramie and then on to Omaha.

Next he telegraphed the good news to Sheridan, requesting, "I wish you would

send him off where he can be out of harm's way." Confident and relieved that the

crisis was over, Crook further remarked, " [T]he successful breaking-up of

Crazy Horses band has removed a heavy weight off my mind and I leave feeling

perfectly easy." Sheridan replied, "I wish you to send Crazy Horse under proper

guard to these headquarters," meaning, of course, to Chicago.

Between five and six o'clock that evening, Crazy Horse, the ambulance carrying

his friends, and the Indian scout-guards reached Camp Robinson. Lee had been

informed beforehand to take Crazy Horse to the adjutant's office. The party rode

in as the evening parade concluded, and most of the soldiers returned to their

barracks. At headquarters Crazy Horse was met by 2nd Lt. Frederic S. Calhoun,

post adjutant, whose late brother James was a brother-in-law of George Custer,

both killed at the Little Bighorn, possibly by warriors led by Crazy Horse.

Lieutenant Calhoun directed that Crazy Horse be turned over to Capt. James

Kennington, the officer of the day. Lee had Crazy Horse and the other Indians,

including Touch the Clouds, go inside the office while he conferred with Colonel

Bradley at his quarters.

Before leaving Spotted Tail Agency, Lee had assured Crazy Horse he would be

permitted to have a few words with the post commander. The well-intentioned Lee

was obviously unaware of what was in store for Crazy Horse at Camp Robinson; his

request for an interview was denied. Increasingly apprehensive Lee returned to

the headquarters office to tell the companions of Crazy Horse that he would

remain at the post under guard until the following morning.

Portentous Darkness Over Camp

Robinson

By now any proposed meeting of reconciliation or explanation between Crazy Horse

and Bradley, or any post officer for that matter, was out of the question.

Crook's plan was to place Crazy Horse under arrest immediately and have one of

the cavalry companies rush him and several of his men to Fort Laramie that

night. Several officers later deduced that he was to be imprisoned at Fort

Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas off the Florida coast. If Sheridan had exile in

mind, he would not have sent Crazy Horse there -- the fort had been abandoned for

two years. A more likely destination was Fort Marion at St. Augustine, Florida,

where southern Plains leaders had been earlier imprisoned. Nonetheless Crazy

Horse and his influence would be effectively excised from the northern Sioux

agencies.

A crowd of several hundred agency Sioux, Indian scouts, Arapahos, and northern

Indians, including Crazy Horse followers, had assembled on the south side of the

parade ground. Red Cloud and his men stood by on one side of the adjutant's

office, while American Horse and his warriors waited on the other. Captain

Kennington, accompanied by Crazy Horse's one-time close associate Little Big

Man, entered the office and escorted Crazy Horse to the guardhouse, some sixty

feet to the west. Infantrymen of the post guard followed and attempted to keep

outsiders from crowding in. As they neared the guardhouse door, some northerners

in the crowd protested Crazy Horse's impending confinement, while other Indians

"insisted on non-interference." Once inside, Little Big Man "now became his

chief's worst enemy.”

Parade ground of original Camp Robinson

where "A crowd of several hundred agency Sioux...had assembled."

The building they entered consisted of two rooms. The main entrance opened into

the guardroom, and to the right was the separate prison room where several

military prisoners were confined. According to Lee, it was the sight of those

prisoners that panicked Crazy Horse.

Crazy Horse, who was still armed with a pistol and knife, drew the latter and

struck out wildly at his captors. This unexpected outburst created instant

confusion among the soldiers and scouts standing inside the guardroom. Little

Big Man immediately seized Crazy Horse's arms from behind in an attempt to

control him. Both wrestled their way out the door. In the ensuing struggle the

knife slashed Little Big Man's wrist or lower arm, he released his grip, and

Crazy Horse broke free. In the next instant, as the noise of the disorderly

crowd rose to a din, one of the guards stabbed Crazy Horse in the right side

with his bayonet. Seriously wounded, the stricken war leader crumpled to the

ground.

Little Big Man was the Lakota who

fulfilled Crazy Horse's vision: Crazy Horse's death could only come at the hands

of one of his own people.

Photo Public Domain

The crowd massed before the guardhouse. As the now alerted garrison stood ready,

some warriors and agency leaders stepped forward and tried to calm the enraged

northern Indians. They largely succeeded. Their quick actions undoubtedly

prevented further bloodshed, when "one shot would have been sufficient to start

a fight."

At this critical juncture, instead of taking the wounded Crazy Horse back into

the guardhouse, he was carried into the more neutral adjutant's office.

Assistant post surgeon Valentine T. McGillycuddy stepped forward to lend

whatever medical aid was possible. While the assemblage of agency Indians and

confused and angered followers of Crazy Horse gradually broke up and returned to

the camps, Touch the Clouds and Worm, Crazy Horse's father, were allowed inside

to comfort him. Lieutenant Clark telegraphed Crook that Crazy Horse had been

stabbed during the attempt to place him in the guardhouse. Because of the wound

it would be impossible to move him that night.

Contradictory versions of how the stabbing occurred were already circulating.

Some thought the wound was definitely caused by a guard's bayonet (which guard

is still debated). Others insisted Crazy Horse had been stabbed with his own

knife during the struggle with Little Big Man. Clark voiced the latter, hoping

this scenario would convince the agency Indians that the army had not

deliberately intended to harm him.

"It Is Good, He Has Looked For

Death And It Has Come."

In the adjutant's office Doctor McGillycuddy, Touch the Clouds, Worm, and others

kept vigil. McGillycuddy immediately realized the wound was fatal and gave Crazy

Horse some medication to relieve the pain. Near midnight, he died. Then his

friend Touch the Clouds reportedly said, "It is good, he has looked for death

and it has come." When the still-mourning Fred Calhoun heard of Crazy Horse's

death in his office, he exclaimed rather triumphantly, "He was forgiven for

murder, but killed for impudence."

Fearing acts of vengeance, the garrison remained under arms, set out pickets,

and patrolled the road toward the agency camps throughout the night. At the

agency itself the employees and mixed-bloods were brought within the protective

stockade. Although considerable excitement and numerous false alarms followed,

no hostile forays against the post or agency were ever made.

The next morning Crazy Horse's grieving father took his son's body back to

Spotted Tail Agency, where Lee returned to prepare for any ramifications from

the killing. For several days turmoil and unrest prevailed, especially among the

northern bands, who made open threats against army officers, including Clark and

Burke. At Red Cloud rumors turned to panic when residents heard that soldiers

and Pawnee scouts would surround the northern camps. Over one thousand northern

people stampeded from Red Cloud Agency to the more amiable atmosphere of the

Spotted Tail camps. The chiefs supportive of the government, including the

controversial schemer Little Big Man, sought to restore order and quiet in the

camps. Little Wound, who stood with the army against Crazy Horse, echoed the

opinion of the agency chiefs when he declared, "We had afire brand among us, and

we've got rid of it.”

On September 9 Clark reported that the excitement had subsided, adding

self-servingly, "Crazy Horse had a wonderful influence and if he had lived it

would have been war for sure." Many in the army shared this view, confident that

the Great Sioux War was now over. In making his final commentary on the episode,

Lieutenant Bourke wrote, "As the grave of Custer marked [the] high-water mark of

Sioux supremacy in the trans-Missouri region, so the grave of Crazy Horse, a

plain fence of pine slabs, marked the ebb." Years later when asked about the

death of Crazy Horse, one Sioux elder replied,

“That affair was a disgrace, and a dirty shame. We killed our own man.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Looking west. Far building is guardhouse where Crazy Horse was bayoneted. His marker is right of guardhouse. The near building is adjutant's office. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Near building is guardhouse. Middle building is adjutant’s office where Crazy Horse died; his father, Worm, and friend Touch the Clouds beside him. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A back view of the adjutant's office.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Front of the guardhouse. Little Big Man and Crazy Horse would tumble outside from the front door where Crazy Horse received his mortal wound.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Office inside guardhouse. The opened door leads to prisoner’s cell. Crazy Horse realized he was trapped, pulled his knife, and fought Little Big Man. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

View looking towards guardhouse office from prisoner’s cell.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Crazy Horse’s marker in front of guardhouse.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now, What To Do With The Agencies

After the threat of outbreak by Crazy Horse's followers and the northern

Indians lessened, the Indian bureau proceeded with its removal program. With all

the Oglalas gathered and subjugated by coercion and decisive military action,

the time seemed right to move them to the long-planned Missouri River agencies.

A week after Crazy Horse's

death plans were finalized for the agency leaders to confer about the move with

the president and department underlings in Washington. The official delegation

from the Nebraska agencies consisted of twenty-three representatives of the Oglala, Brule, northern Indians (Minneconjou and Sans Arc), and Arapaho tribes.

The entourage included dependents, interpreters, and government officials and

numbered over ninety people. Lieutenant Clark and former agents Howard and

Daniels also traveled with the delegation.

The federal government was not the only government entity that wanted to remove

the Sioux from the White River agencies; the state of Nebraska expressed the

same desire. When the northern boundary of Nebraska was surveyed in 1874, the

fact was verified that neither the Red Cloud nor the Spotted Tail agencies sat

on previously designated reservation lands. Agitation began in the Nebraska

legislature for removal. The Nebraskans claimed they had never agreed to the

Indian hunting rights or to restrictions of white travel or settlement in the

portions of their state that were specified by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

The presence of "a horde of lawless savages" in the northwest corner of the

state stifled its settlement and development. The legislature resolved:

“That we call upon the general government and demand that it shall immediately

remove from within the boundaries of the State of Nebraska, the Indian agencies

of Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, and the Indians who have been brought into our

state and located at and about said agencies without the consent of the state.”

The army concurred for its own reasons. Sherman saw the economic and logistic

advantages of the agencies along the Missouri River near Fort Randall, where

"one dollar will go further toward feeding them than four dollars will at the

agencies." Crook and Sheridan favored sites in the Yellowstone country near the

mouths of the Powder or Tongue rivers. There the Sioux could live in lands now

considered undesirable for white settlement; their supplies could still come by

riverboat. Both believed the Indians could be easily convinced to move north.

The Sioux relocation issue was settled in Washington. With the idea of

relocation in Indian Territory out of the question, the Indian bureau applied

pressure to force the Indians' move to locations on the Missouri River. In

councils with President Hayes and Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz the

delegates opposed the move, but compromised and agreed to winter on the river;

in the spring the Sioux could choose to return inland. Actually the Red Cloud

and Spotted Tail Indians had little room to negotiate. Once they agreed to move,

the shipment of supplies to the old agencies ceased. Their food and other

necessities were shipped to Missouri River sites proposed by visiting

commissioners several months before. Dwindling supplies at the Nebraska agencies

would soon be exhausted, and the Indians would have to move posthaste or face

starvation.

After the delegation's return on October 11, the leaders held councils to inform

their followers of the decision. The agency Indians opposed the move, but Crook

told them they had to go. After one council, commander Bradley reported that

although a number of objections were raised, he thought the Indians would go

quietly. He recorded the Indian preparation for the move and his own thoughts:

“I have had a lot of Indians after me all the morning with various wants. Some

for letters showing I think them good men. Some for my picture and some to say

goodbye. All in preparation for their move. I am sorry for the poor fellows.

They are children in our hands and we ought to care for them a little better.”

Years of wishes notwithstanding, the expeditious nature of the decision caught

the Indian bureau wholly unprepared to shift thousands of Indians and their

possessions several hundred miles. The army was called on to assist once again,

and it gathered as many teams and wagons as it could spare. Companies E and L,

Third Cavalry, escorted the Oglalas to their new agency; Company H, Third

Cavalry, was sent with Spotted Tail's Brules. Crook joined the chorus of critics

when he harped, "Owing to the lateness of the season, this march was attended

with much suffering, and the removal itself was the source of great

dissatisfaction to the people of these tribes."

Red Cloud And Pine Ridge

Regardless of such protestations, the Red Cloud Indians left for their new

agency on the Missouri on October 25, 1877. The column numbered about eight

thousand Oglalas and northern Indians and stretched eight miles when on the

march. A large beef herd followed. Due to inclement weather the progress was

difficult and slow. As the Indians left the White River, Bradley confided in his

diary, "I bid them God-speed, and am glad to get them off my hands.”

The Nebraska press lauded General Crook for his role in ridding the state of

Indians:

“General Crook has met with wonderful success in the removal of the Indians,

having exerted a powerful influence among them. Their peaceful removal was

entirely owing to his efforts, and he is entitled to the greatest credit for the

success of the undertaking, which was one of considerable magnitude and beset

with many difficulties. The Indians have learned to respect him as a man and a

peace maker as well as a warrior.”

For the first time in four turbulent years the White River Valley was empty of

Indian people.

With them went the main mission of Camp Robinson. The garrisons at both agency

posts could be substantially reduced, and as early as October the reduction

began. On the first of the month over six hundred soldiers were stationed at

Camp Robinson. During October most of the two, Third Cavalry battalions left;

two companies escorted Red Cloud's people, one company went with the Brules, and

one moved to Fort Laramie. By mid-November the three infantry companies had

left, and the three remaining cavalry companies departed for Fort Laramie, Camp

Sheridan, and Hat Creek Station. By November 30, the garrison of Camp Robinson

consisted only of Company C, Third Cavalry, leaving the post with a total

strength of two officers and sixty-nine enlisted men.

A new mission soon arose. Although Red Cloud Agency was gone, the post still

resided near the Great Sioux Reservation, and thus fit into the army's

post-Sioux war strategy. The army wanted to restrict the Indians to their

reservation and surround it with a ring of military posts. As a result, several

new forts were built in what had been the very heart of Sioux country, and

existing posts were maintained at strategic points. The Indians would always

know the soldiers were nearby.

Camp Robinson Becomes Fort Robinson

Camp Robinson continued to occupy a key location on the Sidney- Black Hills

Trail, still the major route for Black Hills travelers. By 1877 the gold rush

had ended, but the large population in the Hills provided an economic boost to

the region. Freighters hauled daily shipments of freight, from foodstuffs to

massive stamp mills to process gold ore. In 1877 Black Hills trade over the

Sidney trail totaled four million pounds; in 1878 the figure rose to between

twenty-two and twenty-five million pounds, half of the total Black Hills imports

for the year. The continued military presence at Camp Robinson, however small,

was seen as an asset to the Sidney road.

In the late 1870s a few venturesome ranchers started cattle herds along the

Niobrara and White River valleys. Troops at Camp Robinson provided these

pioneers with a sense of security; however, the removal of the agency and the

corresponding troop reduction brought rumors of the post's abandonment. One

concerned rancher, Edgar Beecher Bronson, who operated a ranch five miles south

of the post on Deadman's Creek, heard of the possibility of Camp Robinson's

abandonment in the autumn of 1878. He wrote department headquarters and asked

for verification. Somewhat reassuringly, the adjutant general replied that the

Omaha headquarters knew of no such plan, hinting that the army would continue to

use the post.

The Indian bureau's goal of settling the Red Cloud Indians along the Missouri

River was never achieved. When the Oglala column reached the forks of the White

River about eighty miles west of their proposed agency, many of the former

followers of Crazy Horse and the nonagency faction broke away and headed north.

Red Cloud decided he would go no farther east; his people would winter on the

White River. After it became evident an agency in the Yellowstone and Powder

country was out of the question, the agency leadership, including Red Cloud,

favored a site at the White River forks. In fact, Agent Irwin had recommended

this alternative to the commissioner of Indian affairs back in July. "I could

promise to take them there willingly and indeed gladly." The army firmly opposed

Red Cloud's decision, but the bureaucrats relented. Subsequently the bureau

permitted Red Cloud and his people to locate even farther from the Missouri

River. In the fall of 1878 the Oglalas relocated on White Clay Creek, nearly two

hundred miles southwest of the ill-fated Missouri River agency site. Here the

last agency for Red Cloud's Oglalas was built and given a new name -- Pine Ridge

Agency.

During the summer and fall of 1878 Lieutenant Johnson, formerly an acting agent

for the Indian bureau, oversaw the breakup of the old Brule agency. His

detachment removed buildings and shipped the salvageable lumber to the new Pine

Ridge Agency. Johnson also received beef cattle for government issue to the

Oglalas.

Also in 1878 decisions were made that again proved critical to Camp Robinson's

future. Although the agencies were out of Nebraska, they were not as distant as

had been anticipated. Crook proposed changes for the former agency post and in

April wrote Sheridan:

“As we shall probably have to keep for a long time a post in the country now

protected by the small garrisons at Camp Robinson and Sheridan, I would

recommend that these two garrisons be consolidated at the latter point which, in

my judgement is the better of the two for military and strategic purposes: if

this suggestion meets with your approval, I will cause the concentration to be

effected without delay.”

Although Camp Sheridan was actually closer to the new Dakota agencies, Crook's

recommendation was not followed, and Camp Robinson's life was fortunately

extended.

Camp Robinson was advantageously located for strategic and logistic reasons. The

post was close to the Black Hills and the Powder River country, two areas that

could still lure raider forays. It was relatively close to the railroad and on

the Sidney-Black Hills road. All in all, it was easier to move troops and

supplies to and fro than at Camp Sheridan's more isolated site. Robinson also

possessed a superior location. Camp Sheridan sat in a low creek bottom prone to

flooding. Such was never the problem at Camp Robinson, located on a broad plain

above the White River.

In August 1878 Crook informed Sheridan that if the post was to be retained, it

needed a larger military reservation. He proposed expanding the reservation

boundaries farther to the east and south, "in order that grog shops and other

disreputable places may be removed from the vicinity of the post." Sheridan

agreed and later authorized an enlarged reservation that was four miles square

with the post flagstaff at its center.

The outbreak of the Northern Cheyennes from their Indian Territory reservation

that fall enhanced the value of the post. Field operations against the Cheyennes

validated Sheridan's decision to retain Camp Robinson as a military station: an

army post in northwestern Nebraska was still needed.

On November 8 an order came down from the adjutant general's office in

Washington concerning the official designation of posts in the military

divisions. The order stated that all posts to be permanently occupied by troops

be designated "forts." Temporary posts were to remain "camps." This order gave

division commanders, including Sheridan, authority to make name changes, and it

can be considered the first public confirmation of the retention of Camp

Robinson as a permanent military post. On December 30, 1878, Sheridan issued

General Orders that officially renamed the post "Fort Robinson."

On the next day a board of survey convened to deal with the last remnants of the

old Red Cloud Agency. The board inspected the agency buildings and grounds to

determine the value of the remaining lumber prior to its disposal, a quiet end

to such a tumultuous place. In only four years the post's role had changed from

filling an immediate, temporary need of protecting lives at the agency to

becoming a strategically located, permanent post. Ironically, Camp Robinson had

outlived the agency it was established to protect. The first phase of its

history over, the fort now entered another.

(Back

to Top)

|