| Friends Of The Little Bighorn Battlefield |

The Next Generation In The Study Of Custer's Last Stand |

Jerome Greene |

| • The Battle • Archeology • Memorials • Little Bighorn Store • News • Book Reviews |

|

Webmaster's Note: Jerome Greene presented this walk down memory lane at the Friends of the Little Bighorn Battlefield's first symposium on June 26, 2001. Mr. Greene is a household name for those interested in the Plains Indian Wars. Somewhat like Bob Utley, I became interested in the Custer story in my youth. Although I started working at the then Custer Battlefield National Monument in May of 1968, it was not my first visit there. I was drawn to "Mecca" as a teenager, after reading Quentin Reynolds's stirring juvenile biography of Custer while in eighth grade. Four years later, following graduation from high school in Watertown, New York, and a summer working as an "Indian" at a western theme park in the Thousand Islands area of the St. Lawrence River, I set off for "Mecca." A Thousand Islands friend packed me on the back of his motorcycle down to Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania. From there I bussed to Philadelphia, where I -- wearing jeans, Tombstone boots, Levi jacket, and a big, black cowboy hat -- all purchased at the theme park -- was turned away by guards at the door of "American Bandstand." Another friend transported me to St. Georges, Delaware, where I piled into a Volkswagen beetle driven by an Iranian army general's son for my ride west. Darius Fazlolahee was a student at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater, and I had met him when he and his American family summered in the Thousand Islands. When we reached Stillwater, I was on my own. I hitch-hiked around in a circle before catching a Greyhound bus for Crow Agency, Montana. Enroute, in Cheyenne I brazenly called on the phone a man named T. Joe Cahill, who had been town clerk there in 1903 when they hanged Tom Horn. I think I woke him up because he sounded grumpy to me on the phone.

A Cold Night Near Custer National CemeteryWhen I reached Crow Agency, I hitched a ride up to the battlefield with a Crow Indian man. It was late in the day, and the place was closed by the time I arrived. But in those days the gates remained open, and I managed to walk up to last stand hill and survey the magnificent scene before me that I had only imagined for years. That mid-September night I unrolled my see-through sleeping bag some place in the area between Deep Ravine and the cemetery and proceeded to pass one of the coldest and most uncomfortable nights I can recall. In short, I froze my butt off and didn’t sleep a wink. The next day I visited the museum, then tried walking to the Reno-Benteen site. Somewhere in the vicinity of Medicine Tail Coulee ford I encountered a rattlesnake, and I think that that ended my trek. I spent the night in the Hardin Hotel, which as I recall was something of a dump, and which mercifully burned down a few years later. By now exhausted from my trip to Custer Battlefield, I became homesick. I sold the Polaroid Land Camera my dad had given me as a graduation gift, and for fiftyseven dollars bought a bus ticket for upstate New York. So that is my earliest recollection of Custer Battlefield in the 1960s. My next is when I was a college student at Black Hills State College (now a university) in Spearfish, South Dakota. When I was in the army in Libya I sent away to Black Hills for a college catalog, and they sent me a letter telling me that I'd been accepted -- that's how I ended up in Spearfish. A college friend there had taken a summer job at Devil's Tower National Monument, near Sundance, Wyoming, where I often visited him with my family. What a great job he had, I thought, and I wondered if I might be able to land a summer position with the park service at Custer Battlefield. I knew it would be a dream job if I could land it. Well, early in 1968 I sent an inquiry, then filled out the necessary government forms they sent back, and then waited. Needless to say, I was enthralled when I was selected that spring to be a ranger-historian at Custer Battlefield. At least once before I started, I drove the 220 miles from Spearfish to the battlefield to check out my situation – where I and my family (I had two children at the time) would be living, etc. The first person I met there was Carla Martin, then administrative officer. Later, when I finally started work in late May, I met Bill Henry, the new battlefield historian, Superintendent Dan Lee and his family, along with the maintenance chief, Bill Hartung, and his crew, including Cliff Arbogast. Among the seasonals besides myself were Bob Carr, a school teacher who had worked there for several summers; Wendy Day and Christine Jeffries from Arizona and Idaho, respectively, both recent college graduates like myself. I believe that 1968 was the first year that Custer Battlefield hired women as seasonals. At that time they had their own uniform that was reminiscent of airplane stewardesses' uniforms, complete with little fore-and-aft caps, as I vividly recall and tight skirts. The female rangers were referred to at that time -- and please forgive me -- as rangerettes. As I recall, too, Bill Henry was always trying to date these young ladies, despite the fact that he was their supervisor. Many of you will remember Cliff Nelson. Cliff was also a seasonal ranger, and 1968 was his first year. We worked there together and became very good friends. Cliff went on to spend many subsequent summers at Little Bighorn -- many more than I did. I was there for two more, and Cliff was there for something like twenty-five more summers, I think. Cliff became a junior high school teacher at Seeley Lake, Montana. As you may recall, Cliff was brutally murdered in his home, a tragedy that was only compounded by the disgraceful miscarriage of justice that followed.

Summer of 1968In terms of context, the summer of '68 was a period of national turmoil in this country because of what was going on in Viet Nam. We had endured the killing of Martin Luther King in April, and in June I remember the horror of Bobby Kennedy's shooting and the news the next day that he had died. But I'd rather relate some of the lesser magnitude things that I remember while working at Custer Battlefield in the summer of 1968. One of them regarded smoking while on duty. It's hard to believe today, but I recall all of the rangers at one time or another standing behind the counter in the books sales area -- probably three or four of us at least, standing there between talks and when we're working the desk, and smoking. Everybody was smoking. There would be a great big ashtray sitting on the desk there, and it was brimming with cigarette butts. It's hard to believe today that that actually happened. I remember being outside and smoking, too. Strange. One of the things I remember that had to do with policy in the summer of 1968 was that at that time we did not let people walk on the battlefield. In fact, I remember us using bullhorns on the veranda outside the building to direct people to come back from the area of Deep Ravine, to return to the walks and that it was prohibited to walk out there. We used the bullhorns to call the people back, warning them of the danger of rattlesnakes that would be lurking at every step. There were also wooden signs along the asphalt trails warning visitors of the presence of rattlesnakes in the area. (Those signs might be still there.) I recall the tumult that existed in July or August, 1968, when a copy of Life magazine appeared in which Alvin Josephy castigated the National Park Service for its one-sided presentations at Custer Battlefield, and how he had listened to a ranger put down the Indians there. I must say that during the summer of 1968 there was probably a decided (and perhaps unconscious) military bias in our interpretation, but I don't remember anybody denigrating the Indians in their talks. Maybe it was a sin of omission rather than of commission. I'd like to say that I've become very good friends with Alvin through the years and I think the world of him, but this did cause a flurry of excitement among the staff in the summer of 1968. I was always vitally interested in the Custer story, and in particular I was fascinated with what had happened to Custer's five companies in the area of the hogback ridge and last stand hill, and on my days off I would go out with Bill Henry looking for evidence of where the companies had maneuvered. It was pretty early in the era of metal detectors, I think, but we hoped to find cartridge casings related to the demise of Custer's battalion. And I remember Bill Henry and me lugging this very heavy and bulky World War II mine detector that we found somewhere in the battlefield offices, and we'd cart that thing all over the battlefield trying to find a shell. It used to be very frustrating for Bill, because he would take this unwieldy instrument and wave it over the ground for fifteen or twenty minutes and never got a beep or a signal, and then he would turn it over to me and usually I'd get a beep almost immediately, much to Bill's chagrin. And I don't think that Bill's ever forgiven me for that.

Crazy Horse is Alive and Well in ArgentinaAnother thing I remember during the summer of 1968 was that we used to have a registry ledger just inside the entrance, and we'd ask people to write their names in it and tell us where they were from and to give us feedback comments about their visits. And I'll never forget that somebody had written down their name, and then, I suppose, in reference to the then-emphasis on the military side of things, under "comments" this individual wrote: "What about Crazy Horse?" Well, the very next person filled in the line and under "comments," in answer to the question above replied that "Crazy Horse is alive and well in Argentina." While at the battlefield in 1968, I became a member of the Little Big Horn Associates. The membership was fairly small at that time. They published a newsletter that was mimeographed in the old- fashioned way, and one of the people that I came to know was Pinky Nelson. Pinky was then the editor of the Research Review, and he would come to the battlefield several times a year. He worked for Sherwin-Williams Paint in Seattle, as I recall. I had always wondered, until I met Pinky, why he was called Pinky. Once I saw him, I understood, for he was pink all over. He was an engaging personality, and something of an independent spirit. Every time he showed up at the battlefield, he bought steaks for all the rangers, and so endeared himself to our small park population in the summer of 1968. I can remember sitting out in front of the ranger quarters, with people all around, and cooking the steaks that Pinky always brought for us. In later years, I lost track of Pinky. I thought he had died. But three years ago I received a note from Pinky Nelson now living in Wisconsin. I called him and we had a nice conversation and he seemed to be doing quite well. Among the random remembrances, I recall the number of people that used to like to show up at the battlefield and walk around dressed like Custer, particularly individuals with long blond hair who seemed to think that they bore resemblance to him. They would come up and don a buckskin coat and walk around. Perhaps they still do. Anyway, it always gave one reason to ponder the psychological aspects of the story we were interpreting and how they impacted people differently. Talk about self-aggrandizement!

Andre the Giant!Once when I was tending the museum during lunch hour, I was in the building all by myself. Everybody had gone to lunch. There were no visitors there either. I was the only one there. I was behind the counter in the book sales area, and I looked up and saw a huge man -- a giant -- coming into the building. This man was so big that he had to duck down under the portal to get through the doorway. I couldn't believe my eyes. I don't know if this was the pro wrestler, Andre the Giant, but he could have been. This individual walked through the museum, and while he was in there I was frantically calling about, trying to tell someone -- anyone -- to come and see this, because they wouldn't believe me if they had not seen it themselves. But I couldn't get hold of anybody and the man left. And later, when I told people about seeing a giant after they'd returned to work, they said, "Right, sure you did. Greene, you're full of it." One could not work at Custer Battlefield in the 1960s without making the acquaintance of Kiah and Sally Buckner, who ran Sally's Last Stand, the cafe at the foot of the hill along Highway 212 that also included a Texaco gas station. Ki and Sally became something of legendary fixtures in my mind in the summer of 1968. That was a time when gas station attendants still actually pumped gas for customers, and I'll never forget the image I have of Ki standing there, holding the hose and pumping gas into my tank with a cigarette about half-an-inch long poised in his mouth with an ash about three inches long and ready to drop. We rangers also used to eat occasionally at Sally's Last Stand. In her cafe and gift shop, Sally sold bird-like figurines made from horse droppings and toothpicks, and a large promotional emblazoned in the front window urged customers to buy their Montana birds there. From that point on, I always envisioned Sally creating her birds in between serving up orders of burgers and fries, and my lunches there were never the same again. Back at the battlefield, one of the things I was fascinated by was elderly people (now that I'm becoming one myself, I find it doubly fascinating). I always liked to ask older visitors -- people in their eighties and up -- to name their favorite president. Almost without exception they would name Teddy Roosevelt as their favorite. Once I accidentally antagonized an aged visitor when I posed the question and he replied, "Roosevelt!" and I made the mistake of asking which one. "Why, Teddy!" he bellowed at me. "Not that other goddamned son-of-a-bitch!" I remember one very old man who was up on top of the hill overlooking the last stand area. I talked with him for quite a while, and he told me that he was from Washington, D.C., and that when he was a five-year-old he watched with his parents as President Garfield's funeral cortege passed by. Garfield, of course, had been assassinated in 1881, and this man was about five at that time, which would make him in his early nineties at the time I talked with him. Now to me, that was fascinating.

Watch Out for Flying Arrows!That summer was just a year or less after the remains of Major Reno had been transferred from Washington, D.C., to Custer Battlefield National Cemetery--probably the last place that Reno would ever have wanted to go if he'd had any say in the matter. He was reburied on a comer in the cemetery so that we would pass directly by Reno's grave on our way to or from the museum. Often at night, after a long day, a few of the guys would take a six-pack up to the last stand area and relax and talk for a while. I know for a fact that some of them would pass by Reno's grave on the way home and that some -- particularly the Custer partisans among them --, well, let's just say that they would occasionally share their beer with him. The living history demonstrations. I think that 1968 was the first year that Bill Henry was the chief historian at the battlefield. In that year we inaugurated a series of living history demonstrations. I participated in one of them that was held several times a day. It involved me (despite my height of 6'3") wearing the apparel of a Seventh cavalryman, circa 1876, and I would discuss the life of a cavalry soldier -- what it was like to serve at the time -- and I would discuss the Sioux War of 1876 as it involved both the cavalry and the Indians. The demonstration would be capped off with a firing demonstration in which I fired a number of blank rounds in an original period carbine. These demonstrations took place out on the east side of the building under the veranda with that metal roof, and I always made sure when I got ready to fire the weapon for the first time, that I stepped up so that I was under the edge of the veranda when it fired. It always boomed and reverberated and scared the hell out of the people, and I got something of a charge out of that. The first round fired was the signal for a number of Crow Indian boys who were hired for the purpose and who wore breechclouts and moccasins similar to the Indians of the 1876 period. Ironically, the Crows were not portraying Crows of the period, but rather Sioux and Cheyennes. At the first fire of the carbine, that was their signal. They had been waiting down in the grass and sagebrush all during the talk -- and at the first carbine fire they began an approach firing arrows at me.

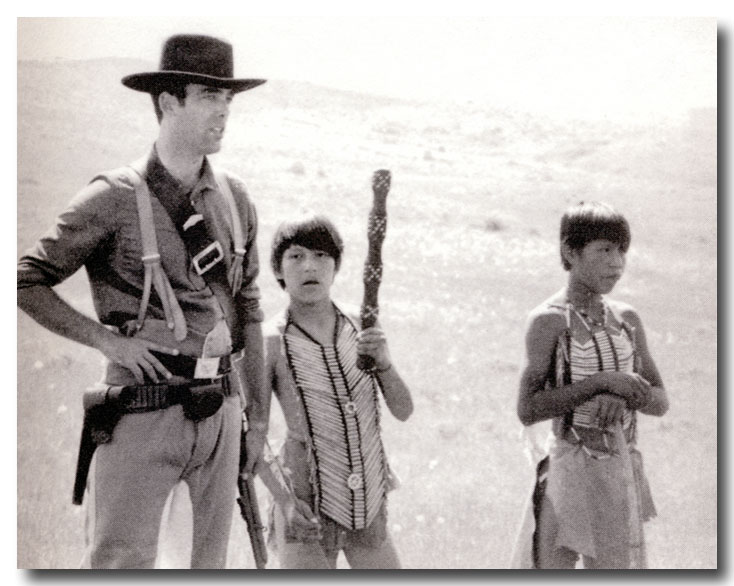

Wearing his interpretive gear, Greene stands beside the Crow boys anxiously waiting for their next chance to lob arrows into the crowd -- photo courtesy of Jerome Greene

Now I have a couple of things to interject here. The arrows were equipped with rubber tips, pencil erasers, so that, ostensibly, no one would be injured. These Crow boys, who were probably eleven or twelve years old, liked to go inside the museum offices between the demonstrations and throwaway the erasers and insert the arrow tips in a pencil sharpener to point them. That made for interesting experiences out there under the veranda, where the angle of the arrow-fire was such that on more than one occasion in between carbine shots I found myself batting down missiles that were flying directly toward the audience. So there are probably some people around the world today whose lives I saved, or at least I prevented some substantial injury to them. That was one thing that I've always remembered about those demonstration. Finally, one event that I'll never forget in the summer of 1968 was the day that my hero, Bob Utley, then chief historian of the National Park Service, showed up one afternoon with the Director of the Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, Ernest Allen Connelly. Of course, I well knew of Bob Utley. Everybody knew of Bob Utley. Everybody was excited that he came to the battlefield that day. I didn't know much about Ernest Allen Connolly, but I know now with what esteem he is held in Bob's mind. When these two gentlemen showed up, somebody was to give an interpretive presentation, and I was the one who was selected to give it. You can imagine how I felt. My nerves were just a little bit frayed as I went into the observation room and stood behind the topographic map and began my presentation with Utley and Connolly sitting in the middle of the room. A few other people were there, too --all tourists. Well, my talk probably lasted about twenty or twenty-five minutes. It wasn't very long, but it was long enough to put Ernest Allen Connolly to sleep. I must say that I would have been mortified had Bob Utley gone to sleep listening to me. But he didn't, and he came up in the gracious way that Bob always does things, he complimented me on my talk. And it made this young ranger feel like a million bucks. And Bob, I don't know if you remember that, but I certainly do, and if my service at the battlefield meant anything to me, your presence and encouragement at that particular time was a defining moment in the summer of 1968. I have many other memories of Custer Battlefield. I was a seasonal there in 1970 and '71, too, but that time was beyond the period of my speaking assignment. Some of the people I worked with then were Cliff Soubier, John Miller (now Father John Miller), Dan Magnusson, Jack Old Horn, and Ben Irvin (whose alter ego is now Colonel Absaraka Ben). So I won't tell you about the time Bennie blew away the rattlesnake at Reno- Benteen with his .35 Magnum special in full view of the park visitors; or of the trail ride from the Crow's Nest that resulted in Soubier's horse rolling over in a stock pond and practically drowning him. I guess that those stories will have to wait until the 150th anniversary in 2026. Thank you! Published by permission of the author, all rights reserved. More Reflections on LBH HomeNews & Information Home |

|

|||

|

Copyright 1999-2016 Bob Reece Friends Little Bighorn Battlefield, P.O. Box 636, Crow Agency, MT 59022 | Home |

Board of Directors |

Guest Book | Contact | Site Map

| |

||||