| Friends Of The Little Bighorn Battlefield |

The Next Generation In The Study Of Custer's Last Stand |

Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee |

| • The Battle • Archeology • Memorials • Little Bighorn Store • News • Book Reviews |

HBO's Bury My Heart At Wounded KneeProduced by Dick Wolf & Tom ThayerDirected by Yves SimoneauWritten by Daniel GiatEarly Movie Review by Bob Reece, May 10, 2007Cast:Aidan Quinn as Henry Dawes; Adam Beach as Charles Eastman; August Schellenberg as Sitting Bull; J. K. Simmons as Agent McLaughlin; Eric Schweig as Gall; Wes Studi as Wovoka; Colm Feore as General Sherman; Gordon Tootoosis as Red Cloud; Fred Thompson as President Ulysses S. Grant; and Academy Award winning actress Anna Paquin as Elaine Goodale Film premieres on HBO May 27, 2007 at 9:00 PM (EST)Update September 16, 2007, Emmy Awards Won: Outstanding Made For Television Movie; Make-up For A Miniseries Or Movie (Non-prosthetic); Single-camera Picture Editing For A Miniseries, Movie Or Special; Sound Mixing For A Miniseries Or Movie Or Special; Sound Editing For A Miniseries, Movie Or Special; Cinematography For A Miniseries Or MovieAll photos from "Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee" courtesy HBO Films. Dee Brown’s book, Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee was one of the earliest books of American history that had mass appeal. It introduced many readers to the past world of the American Indian while fueling the American Indian Movement. As Megan Reece reported in her undergraduate history thesis, “The Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument and an Indian Memorial After 1988”: […]its popularity meant that people who had known almost nothing about American Indian history, now had a complete overview of Indian life. As renowned historian Paul Hutton said, Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee was the “single most influential book about Western history.” The books influence was so drastic that it seemed as if one day, white Americans knew nothing about the American Indians, and the next day, they knew everything.[…] Robert Utley pointed out that (the book) “launched red power.” (page 21-22)

As the book’s popularity grew on the world stage, there followed countless rumors of movies based on the book. While working at Boulder, Colorado’s public radio station, KGNU-FM in 1981, I met the American Indian actor Will Sampson who played Chief Broom in the movie, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Sampson told me that he and Peter Fonda were raising money to produce a 10-hour television masterpiece from the book. Sampson planned to portray Sitting Bull. Peter Fonda would have a major part and possibly his father, Henry. It never came to pass: Henry died, the money did not materialize, and sadly, Sampson died from complications due to a lung-heart transplant. Finally, three decades after the book’s publication, HBO brings to cable television “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.” It is not a mini-series; in fact, it only covers the last two chapters of Brown’s book and runs a little over two hours. The film might have been titled, “The Last Days of the Sioux Nation.” At the outset, let me state for our visiting history buffs that there are many historical inaccuracies in this film; some are big, and some are small. Director Yves Simoneau recounts the story of reservation life, the taking of Indian lands and the debate that ensued. Choosing drama, as opposed to a documentary style, to recount these subjects is most challenging. Writer Daniel Giat has molded the multifaceted characters from a composite of many. I’ve always been able to look past the inaccuracies within historical dramas to enjoy a movie for what it is. When one looks past the inaccuracies in “Wounded Knee”, one will discover many moments of brilliance. So, let us undo some of the most important snafus first:

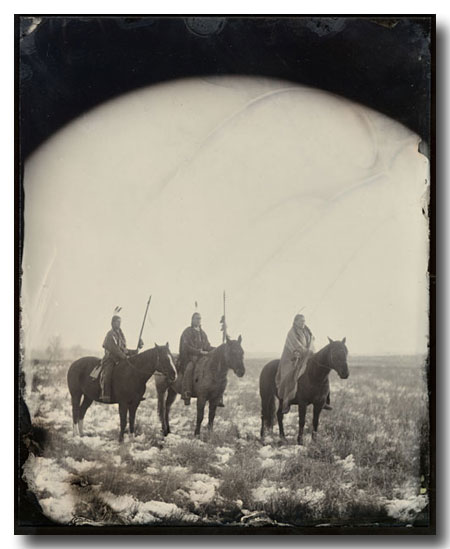

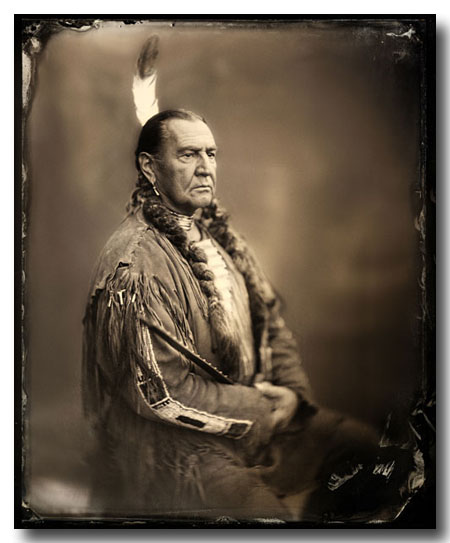

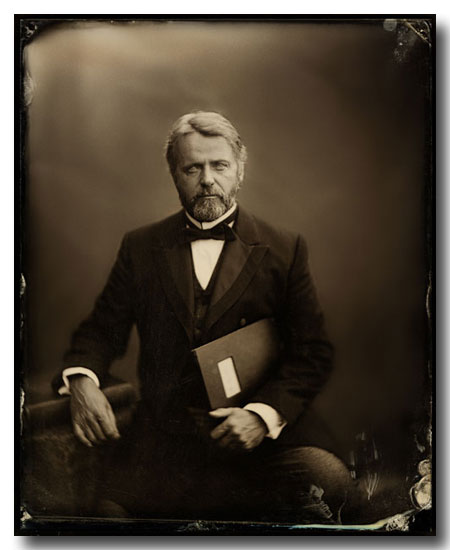

Filmed entirely in Canada, the movie opens with the Battle of the Little Bighorn along rocky pine-strewn countryside. Custer and his officers are never seen. Instead, in one short powerful scene we follow overhead warriors on horseback as they race out of their village to fight Custer. The warriors and their mounts slowly dissolve into CGI figures as they cross the Little Bighorn River to meet Custer. The soldiers are in a big circle with all the warriors racing around them on horseback. If you look carefully, you'll see a brown speck near the center. Is it Custer? Is he still standing? Although the scene is not realistic, it does capture the concept of the last stand relatively well. The film revolves around the principal characters: Sitting Bull (Schellenberg); Charles Eastman (Beach); and Senator Henry Dawes (Quinn). There is also one main character we never see: it is the despair of a dying culture as the Lakota nation gives up its old way of life. This desperation is felt throughout and never lets go its grip of the viewer. The film contains episodes of brilliance and astounding beauty. At its center is a recalcitrant question of Indian adaptation into the white man’s world. Should the Indian become completely assimilated as Dawes suggests? Dawe’s motives are pure and good, however, he still sees the white man as superior to the Indian. The Beach character is Indian, yet he lives comfortably in his new world; he wears the white man’s clothes, he becomes a physician, and he marries Goodale (Paquin), a white woman. Is the film intended to sanction the required assimilation in order to survive, or to embellish and regret it? “Wounded Knee” indeed seems to be two films. The first covers the latter years of Sitting Bull’s life which are filled with triumph and defeat, greatness and loneliness. The second involves the rescue of a culture gasping its last breath. Trying to resuscitate it are Dawes and Eastman through the building of the Dawes Act that ensures every Indian family would own 160 acres of land. Film one is the story of Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull, resolute and alone, a defeated chief of the Lakota, is one of the most convincing American Indian characters ever shaped for a film. He is a complete enigma. He fights to protect his people, yet he lashes warriors for fleeing Canada to their homeland in the Dakotas. He criticizes other Indian leaders for accepting the white man’s way of life, yet he sells his autograph and photo.

August Schellenberg as Sitting Bull In one courageous scene, Col Nelson A. Miles (Shaun Johnston) and Sitting Bull are in a tense negotiation just before the skirmish at Cedar Creek in October 1876 (shown as a full blown battle in the film). Miles challenges Sitting Bull’s account of the Lakota people as champions of the plains. “The proposition that you were a peaceable people before the appearance of the white man is the most fanciful legend of all. You conquered those tribes, lusting for their game and their lands, just as we have now conquered you for no less noble a cause.” Sitting Bull exclaims, “This is your story of my people!” Miles responds, “This is the truth, not legend.” Agent McLaughlin (Simmons) and Gall poignantly acted by Schweig will also later, and in separate scenes, chastise Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull’s redemption is intended to be shown in one dramatic scene where he confronts the Dawe Commission. “You may say they wish to give us land. But, here is the truth. Each patch is for a man and all generations that follow. They know that this land cannot feed but one generation, not even so much as that...” He continues his speech which will shock and surprise many viewers. In the end, Sitting Bull's oration becomes his death warrant. Here, Sitting Bull also becomes Christ like; he is willing to die so he might save his people. Film two follows the life of Eastman. When he is 15 years old, his father Jacob (Wayne Charles Baker) returns only to take him back from the roaming Santee bands. His father’s short hair and white man’s clothes confuse the young Eastman. Even more confusing is his father’s acceptance of Christianity and his singing of hymns. The father knows how to save his son. Eastman travels east with his father and enters school. He excels to the point that he is sent further east to better schools. For me, one of the most notable scenes occurs when Eastman must leave his father to begin yet another new life. As Eastman looks out the window of his slowly moving train, his father waves goodbye and begins to sing a hymn. The emotions are exceedingly powerful; the hymn develops into an Indian strong-heart song as he waves goodbye to his son for the last time. Eastman excels even more, eventually becoming the agency physician at Pine Ridge. He meets Goodale and they become fast friends. It is understandable; Goodale was extremely bright, she spoke fluent Lakota, and she was a member of Friends of the Indian. However, the Beach character is filled with conflict in one of his best performances. Living again among his people, Eastman questions what he has become. Although not addressed in the film, he and Goodale, many years later, would end their marriage in a secret separation. One has to wonder if the conflicts told so well in the movie were the cause of this sad ending.

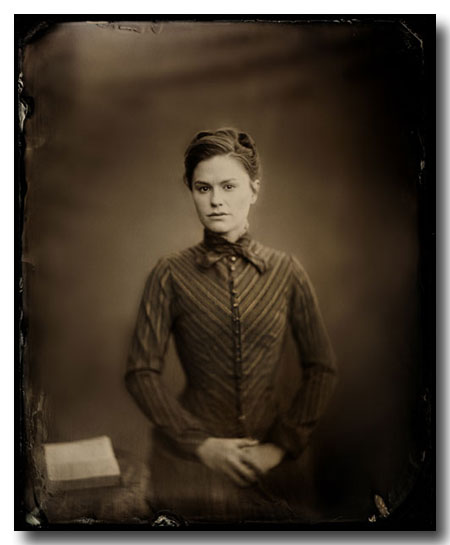

Anna Paquin as Elaine Goodale From these doubts, the film chronicles perfectly Eastman and Dawe’s collapsing relationship. Through the first two acts, they share the enthusiasm of great dreams and aspirations on how they intend to save the American Indian. They become like father and son. But, they finally reach an impasse in a scene that exudes much sadness.

Aidan Quinn as Henry Dawes In the middle of this complex storyline comes a moment of elegance in the only scene involving Wovoka (Studi). With ballet like movements, the Studi character brings his message of the Ghost Dance to the Lakota people. As he articulates his vision in words, he accompanies them with Plains Indian sign language while his body gracefully moves before the crowd. Wovoka’s message is simple: If the Lakota people believe his vision and learn the Ghost Dance, the Great Spirit will rid the earth of the white man, return the buffalo to their full glory, and give back to the Lakota their old way of life. It is the strangest irony of this film: from such promise the Lakota people feel happiness again, but all they receive is death. “Wounded Knee” gives us two great scenes that connect the two films together. The first is the death of Sitting Bull never told before with such accuracy in any other film. This scene over any other still haunts me. Sitting Bull dies for his people but he cannot save them. The film then transports us to the second climatic scene, which is the Battle of Wounded Knee. Yes, it was a battle; there was fierce hand-to-hand combat, and it ended in a slaughter. The movie vividly portrays the tension leading up to the battle, its fight, and its massacre, but fails in its explanation why. The movie attempts to explain as when Col. James Forsyth (Marty Antonini) says to Eastman, “We didn’t fire first. I swear to all-mighty God, we did not fire first.” I still wish the film explained further. That lack of explanation does not diminish from the greatness of this movie. It is truly courageous in the tale movie producers have, until now, been afraid to touch. For the first time we have a Western movie that is concerned with both sides. With its intelligent script, strong direction, and powerful acting, “Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee” grasps the concept of the last days of the Lakota nation wholly; at times brutal, but the movie still exhibits warmth and passion. Final Thought: There are strong performances from the entire cast, especially Beach and Schellenberg who must carry the weight of the film upon their shoulders. Beach’s role comes after an incredibly strong performance as Ira Hayes in Clint Eastwood’s film, “Flags of Our Fathers.” Beach’s performance in “Flags” was overlooked of a well-deserved Oscar nomination. His role of Eastman should garner an Emmy nomination, as should Schellenberg’s of Sitting Bull. Books On The Horizon Home |

|

||

|

Copyright 1999-2013 Bob Reece Friends Little Bighorn Battlefield, P.O. Box 636, Crow Agency, MT 59022 | Home |

Board of Directors |

Guest Book | Contact | Site Map

| |

|||